×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Kathy DeGagne, BFP Staff Writer

A cruise liner gently bumped against the wharf at the mouth of the Yangtze River in the late spring of 1939. The ship had voyaged 8,000 miles [12,874.75 km] from Italy, and the people on board—Jews from Germany—stood at the rail, gazing on the scene before them with trepidation and excitement. Shanghai had been their last hope. Here they were, safe in a country that had opened its arms to them when almost every other nation in the world would not.

A cruise liner gently bumped against the wharf at the mouth of the Yangtze River in the late spring of 1939. The ship had voyaged 8,000 miles [12,874.75 km] from Italy, and the people on board—Jews from Germany—stood at the rail, gazing on the scene before them with trepidation and excitement. Shanghai had been their last hope. Here they were, safe in a country that had opened its arms to them when almost every other nation in the world would not.

Just six months before, a violent demonstration of anti-Semitism called Kristallnacht (the Night of Broken Glass) had raged across Germany and Austria. It was a wake-up call to German Jewry of the menace of Hitler’s regime. Some 30,000 Jewish men were arrested after Kristallnacht and sent to concentration camps. However, they could obtain release if their families had tickets for passage out of the country. Some chose to flee their German homeland immediately; others waited too long or could not get visas and found themselves trapped.

Shanghai and the Dominican Republic were the only nations that did not require entry visas for those seeking asylum. The United States, Canada and all other western nations refused to accept more refugees beyond their set immigration quotas, closing their ears to Jewish pleas for help. Over 20,000 Jewish refugees had no choice but to flee halfway across the globe to Shanghai. The refugees boarded ships bound for a city synonymous with freedom.

When they docked at Shanghai, a wave of oppressive heat and humidity almost knocked them over. Dressed for a European climate in their woolen suits, fedoras and coats, their initial excitement turned to utter misery. The port was filled with a cacophony of Chinese voices and choking traffic, a bustling opium trade and the unspeakable smell of stagnant sewage. Smallpox and cholera raged through the city.

More shocks were yet to come. The refugees were loaded onto flatbed trucks and taken to a Jewish refugee center called a heim (German for home) provided by the Jewish population already living in Shanghai. Large rooms crowded with bunk beds were prepared to house 400 people—with no privacy and inadequate washing and toilet facilities. The refugees would be housed and fed breakfast and lunch until they could rent their own lodgings. They had been allowed to leave Germany with only 10 marks (US $2.50). To get money for rent, they were forced to sell everything they had—pots, utensils, fabric, hats, coats. Harsh reality set in and many regretted their decision to leave Germany.

However, Jewish resilience soon took over and both men and women started small businesses, learned the language or pidgin English to communicate with the Chinese vendors and established homes in the buildings lining the narrow alleyways of Hongkew, a desperately poor section of Shanghai where housing was cheap. Ten people often had to cram into one room. But as they got settled and found jobs, despair turned to hope, and they were grateful they had escaped Europe in time. News was trickling back from the continent and they learned about the horrors their families were facing.

However, Jewish resilience soon took over and both men and women started small businesses, learned the language or pidgin English to communicate with the Chinese vendors and established homes in the buildings lining the narrow alleyways of Hongkew, a desperately poor section of Shanghai where housing was cheap. Ten people often had to cram into one room. But as they got settled and found jobs, despair turned to hope, and they were grateful they had escaped Europe in time. News was trickling back from the continent and they learned about the horrors their families were facing.

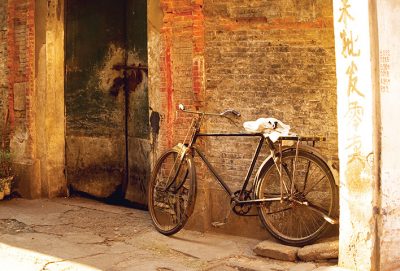

As the refugee families settled in, they found their Chinese neighbors to be exceptionally kind without a hint of anti-Semitism. Chinese and Jewish children played together in the alleyways lined with bicycles and wooden crates. For the children, life was a fascinating parade of sights and sounds.

The area where most of the Jewish population was concentrated eventually became a cultural center called Little Vienna. The streets were lined with Viennese-style cafés, shops, bakeries and nightclubs. Jewish cultural life flourished with operas, theater and concerts. The refugees established Jewish schools, sports fields, synagogues and Jewish newspapers.

However, the geopolitical situation in Shanghai was tense. Parts of the city were under Japanese occupation and the Japanese Imperial Army was itching for another fight. Pearl Harbor was their next target, and the war in the Pacific began, paving the way for the long arm of Hitler to reach the city.

Fears spread that the Final Solution was coming to Shanghai when Nazi officers arrived in the city. Rumors were that they had brought a canister of Zyklon-B with them to train the Japanese in the mass extermination of the Jews. Some heard that a leaky ship was to be loaded with Jews, taken out to sea and scuttled. Dread rippled through the Jewish community.

Eventually, all Jews who had arrived after 1937 were ordered into a unwalled ghetto, comprising a 1 square mile (92.5 square km) part of Hongkew, the only indication that Japan had listened to the Germans’ demand to deal with the Jewish population. It was a 1-square mile (2.5-square km) part of Hongkew. They had to obtain passes to go outside the ghetto from an arrogant Japanese official named Ghoya, who referred to himself as “The King of the Jews.”

Though ghetto life under the Japanese was irksome with some incidents of brutality, it was a far cry from the walled ghettos in Europe. Compared to the British, Dutch and Americans in Shanghai who found themselves under Japanese detention, the Jews lived in relative freedom and found opportunities to secretly lend aid to their friends.

When the war in the Pacific ended, blue and white banners emblazoned with the Star of David flew over the ecstatic ghetto. Most of the Jewish refugees—Shanghailanders, as they came to be known—emigrated to the United States, Israel and Australia. Many eventually returned to Shanghai to thank their Chinese hosts.

For 20,000 desperate Jewish people trapped by a world flooded with madness, Shanghai was a city of refuge—an Oriental “Noah’s Ark.” Neither Israel nor the families who found sanctuary from the storm will ever forget.

Photo Credit: Click on photo to see photo credit

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2024.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.