×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Abigail Wood, BFP Staff Writer

Photo Credit: Stepan Kapl/shutterstock.com

When I first began learning Hebrew, my teacher continually had to correct my prepositions and conjunctions because I always set single-letter words apart from the words they were modifying or connecting. What I learned at last was that no Hebrew letter ever stands alone. If it’s a single syllable, it is either connected to what it modifies or it is given a friendly silent consonant to keep it company.

This is a metaphor for Jewish community. No single member of the community stands alone. The strength and health of the community depends on the actions, joys and pains of the other members. While this may be the traditional Jewish view of community, it is hardly common in the modern world today. The general tendency is toward individualism and away from corporate accountability. Community and corporate movements are quickly labeled “socialism” and dismissed, much to the detriment of true spiritual community.

Photo Credit: gpointstudio/shutterstock.com

The idea of radical individualism that permeates secular culture today appears even in the Christian Church, where self-help book titles offer slogans such as The Prosperous Soul: Your Journey to a Richer Life, and Safe People: How to Find Relationships that are Good for You and Avoid Those Who Aren’t. With all the “you” and “your,” some sections of the local Christian bookstore begin to look like the cover of Self magazine, offering pithy hints and exhaustive research studies on how we as individuals can improve ourselves. Because, in the end, it’s all about being the best version of ourselves, isn’t it? Hardly.

The self-centered titles mentioned earlier display an obsession with the individual that is destructive to both the Jewish and Christian ideal of true spiritual community. In fact, one of the central pillars of Christianity is the belief that we are insufficient to save ourselves from our own sin nature. Centering our thoughts and efforts on giving ourselves regular spiritual “makeovers” shifts the focus from the Lord to our own strengths and failings. As a side effect, this brand of navel-gazing distracts us from the community around us.

It is difficult to overstress the significance of living in community as seen in both the Tanakh (Gen.–Mal.) and the Writings of the Apostles (Matt.–Rev.). From the very beginning, men, created in God’s image, have been sharers in God’s communal nature and are called to live in relationship with not just God, but with each other as well. In Genesis God said, “It is not good that man should be alone” (Gen. 2:18a). In a well-known verse in Psalms, the Word expounds on this idea, detailing how man ought to behave in community: “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!” (Ps. 133:1).

It is important to understand the responsibility of the individual in the kingdom of God. Ezekiel 18 specifically says that if a man is truly good, righteous and honest, then he should not suffer for the sins of his son nor the sins of his father. “The righteousness of the righteous shall be upon himself, and the wickedness of the wicked shall be upon himself” (Ezek.18:20b). It is clear in the Christian faith as well that salvation must happen on an individual basis. No parent or child can force their loved one to believe in Yeshua (Jesus).

And yet, Scripture is filled with examples of the nation of Israel turning as one back to God or as one falling away from God. We see an entire family condemned for the rebellion of Abiram and Dathan in Numbers 16, and in Acts 16 we see the guard’s whole family saved when he believed in the Lord and the members of his household were baptized as a result. The actions of the one, though certainly deserving of individual judgment, also affect––sometimes quite drastically––the lives of those in the community.

Community is also necessary to fulfill the law of God. In the Ten Commandments, for example, other than the commandments covering our relationship with the Lord––we are not to make graven images, take the Lord’s name in vain, or follow other gods––every commandment requires a community to fulfill. Honoring our father and mother, keeping the Sabbath, abstaining from murder, avoiding lust and theft, bearing false witness and coveting, all involve the way we interact with our community. Certainly, sins amongst the community have negative effects on the individual soul as well, but these commandments assume individuals are living in fellowship.

Photo Credit: Syda Productions/shutterstock.com

What is a community? Mordecai Kaplan, in Basic Values in Jewish Tradition, defines a community as “a form of social organization in which the welfare of each is the concern of all, and the life of the whole is the concern of each.” The concept of community is central to Judaism, because it is directly linked to the Jewish concept of God.

Milton Steinburg writes in his book Basic Judaism that Jewish tradition holds that all partake of God and, because of that, none can be excluded from kindness and respect. He claims there are no limitations to this. “I cannot respect my fellow excessively,” he writes. “On the contrary, since he contains something of God, his moral worth is infinite.” Simply put, the idea is that each individual is a refraction of the light of God. The Jewish tradition holds that, as individuals are bound to each other by common descent from the oneness of God, our unity runs deeper than any differences and we are all, as Steinberg puts it, “brothers in God.”

David Sears also speaks of this in Compassion for Humanity in the Jewish Tradition. He writes that all men, created in God’s image as stated in Genesis 1:27, are in and of God. Jewish men bind the tefillin (square leather box containing the Shema) to their head when praying, in accordance with the command given in Deuteronomy 6. The Shema reads: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one! You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your strength” (Deut. 6:4). Therefore, whenever a Jewish man prays, he binds to his head and arm the idea of echad, oneness. Sears says: “There is a deeper reason why it is important for all nations of the world to relate to this distinctively Jewish precept. The tefillin uniquely expresses the mystery of God’s Oneness, which, by definition, encompasses all that exists.”

There is a radical equality in Judaism. Every man, though created uniquely by a God of details, carries in himself not only the fingerprint of his Maker, but a part of His nature as well. The aspects of man that compose his unique personality are a gift from the Maker, but do not originate in him. Rather, as Kaplan says, they “come to a focus, as it were, in him, but they exist in God.”

Gilad Shalit saluting Prime Minister Netanyahu after landing in an IDF base post-rescue Photo Credit: IDF/wikipedia.org

A good example of this Judaic idea of community appears in the events surrounding the capture and release of Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier held captive by Hamas for more than five years until his release in 2011. The release of Shalit carried with it a great cost––Hamas set him free in exchange for 1,027 Palestinian prisoners, many of whom were murderers and terrorists who returned to their former ways after being released from prison. Why would Israel agree to release such a monumental number of dangerous men and women for the return of a single Israeli? Regardless of political and social opinions on the highly-contested deal, one thing was clear––Israel was willing to lay it all on the line for one lost soldier because Shalit was, for the country, the son of every mother and the brother of every sister. His loss was a loss to the community as a whole, not only to a single family.

This mindset makes perfect sense through the lens of Hebraic roots. Everything is connected and, unlike the Hellenistic categories that arose out of a Greek way of thinking, nothing can be disconnected from what surrounds it. Faith is in and through everyday life; nation is affected and upheld by the individual; and one lost soldier in Hamas captivity has the power to command the eyes and hearts of an entire nation.

However, such an intricately connected community allows for communal failing as well as triumph. In the Jewish tradition, a community that can be corporately righteous in the eyes of God can also fall corporately, even at the hands of an individual.

There is a rabbinical parable about men floating adrift in a boat at sea. One draws forth an awl and begins to bore a hole into the bottom of the boat. The rest of the men, understandably alarmed, cry “Stupid one! What are you doing?” The other answers: “And what concern is it of yours? Is it not under my own seat that I am making a hole?”

The story illustrates how the actions of one man can destroy an entire community. There is no such thing as “personal” or “private” sin—our sin will bring down the entire boat if we persist and refuse to repent.

While the Torah (Gen.-Deut.) assures us that “Fathers shall not be put to death for their children, nor shall children be put to death for their fathers…” (Deut. 24:16), God warns of generational punishment multiple times throughout the Torah. In Exodus 20:5, while proclaiming the Second Commandment, the Lord declares that He is a jealous God, “visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate Me.”

While the Torah (Gen.-Deut.) assures us that “Fathers shall not be put to death for their children, nor shall children be put to death for their fathers…” (Deut. 24:16), God warns of generational punishment multiple times throughout the Torah. In Exodus 20:5, while proclaiming the Second Commandment, the Lord declares that He is a jealous God, “visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate Me.”

The Tanakh holds multiple examples of the generational effects of sin against God, including the familiar sin of David and Bathsheba leading to the death of their son. Another, earlier example of punishment upon an entire family appears in Numbers 16, when the Lord visited judgment upon the tents of Dathan and Abiram, men who joined Korah and rebelled against Moses and Aaron in the desert. The Lord told the people to move away from the tents of the two guilty men, and the men emerged from their tents with “their wives, sons, and their little children” (Num. 16:27b). Before all Israel, the ground opened beneath the men and their entire family and “swallowed them up, with their households and all the men with Korah, with all their goods. So they and all those with them went down alive into the pit; the earth closed over them, and they perished from among the assembly” (Num. 16:32–33).

Why was this drastic punishment visited upon the families as well as the two rebels themselves? Because families and communities are intrinsically linked in Judaism. The wrongful incense burning of Korah and the rebellious response from both Dathan and Abiram did not arise spontaneously out of a community that served the Lord wholeheartedly. Their sin, allowed to grow unchecked by their community, cast guilt upon their entire community when it came to fruition. They did not sin alone, because their community had failed to nurture a heart of godliness.

Photo Credit: GWimages/shutterstock.com

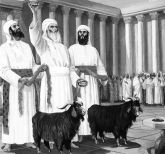

This idea of communal sin and repentance is central to Judaism. The annual observance of Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is deliberately set apart as a day to seek God’s pardon corporately as well as individually. During Yom Kippur, the community fasts in repentance before the Lord, ceasing work and devoting their time to extra synagogue services. This fast is a culmination of the Ten Days of Repentance which begins on Rosh HaShanah (Jewish New Year)—repentance not only as an individual but as a nation and community as well. The first occurrence of corporate atonement came as a result of the sin of the people of Israel when they created the golden calf while Moses was upon Mount Sinai. It was a nation-wide, community-wide sin, and it demanded corporate recompense. Like an individual, the community has a righteous or wicked identity and can be rewarded or punished based on that identity.

Photo Credit: www.iStock.com

The idea of echad (Hebrew for “one”) appears, of course, in the Christian faith as well as in Judaism, with exhortations regarding community and unity surfacing over and over in the Writings of the Apostles. Paul writes, “For as we have many members in one body, but all the members do not have the same function, so we, being many, are one body in Christ, and individually members of one another” (Rom. 12:4–5). This is virtually the same as the Jewish idea of oneness through our equal share in the divinity, except that Christians have Yeshua as their uniting Head: “And He is the head of the body, the church, who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead, that in all things He may have the preeminence” (Col. 1:18).

Paul also writes in 1 Corinthians 12:13 that we were all baptized into one body, regardless of being “Jews or Greeks, whether slaves or free.” The result of this baptism into the body of Christ is a call to practically act toward each other as we would toward ourselves. If one part of the body is failing, then the entire community suffers––just as the whole boat sinks if one man bores a hole under his seat. Paul speaks strongly about division in the body, exhorting believers to care for one another. “And if one member suffers, all the members suffer with it; or if one member is honored, all the members rejoice with it” (1 Cor. 12:26).

Fighting within the body of Christ, then, is particularly needless––like a body attacking itself through an autoimmune disorder. Such behavior both weakens the body and distracts it from doing what it was made for. As Christians, we are meant to look out into the larger community to serve and honor those around us, and, through that service, to bring glory to God. The Body of Christ is often tempted to attack itself through infighting, quarrels, and gossip. Gossip, in particular, is a pollution of what true community should be. True community encourages a healthy care and interest in the people around you, while gossip takes this to a self-serving level, encouraging shared information and tidbits of stories for the sake of the gossiper’s own self-importance. Thus, ailments within the body must be tended to so that the function of the body is smooth and undivided.

It is critical that the Body of Christ is strong enough in and through Christ to overcome infighting in community, because Christians are not only called to minister to those within their body since they are to be in unity before God. They are also to care for the poor and needy and provide comfort for the fatherless, regardless of whether or not those in need are as yet baptized into the Spirit.

Just as Isaiah says, “If you extend your soul to the hungry and satisfy the afflicted soul, then your light shall dawn in the darkness, and your darkness shall be as the noonday” (Isa. 58:10), similarily the Gospels exhort believers to give freely of themselves. “I have shown you in every way, by laboring like this, that you must support the weak. And remember the words of the Lord Jesus, that He said, ‘It is more blessed to give than to receive’” (Acts 20:35).

Photo Credit: DWilliams/bridgesforpeace.com

Close community alters views on traditional ideas of charity and compassion. As Milton points out, the Jewish tradition sees charity as more than simple compassion, but as “rectification for communal failure.” One of the Hebrew words for charity is zedakah, which means not only helping the poor, but also translates as “righteousness.” The idea is that charity as a community actually redeems the community in part and restores some of the community’s lost dignity.

The Hebrew word for compassion is racham, which is very close to rechem, meaning “womb.” Compassion is closely linked to “mother-love”—if a child suffers, so does the mother. The mother will sacrifice anything for her child not only because she sympathizes with their pain, but because she also empathizes. Sympathy, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, is “the feeling that you care about and are sorry about someone else’s trouble, grief, or misfortune.” That’s certainly admirable, but empathy takes caring to an entirely new level. Merriam Webster defines empathy as “the ability to share in another’s feelings.” Empathy, then, is not merely feeling sorry for someone––it is quite literally feeling the same pain with another person.

Photo Credit: DWilliams/bridgesforpeace.com

This is the mother-love of compassion. A mother is able to enter into her child’s pain and take it as her own. It is not the action of feeding the needy or caring for the fatherless that is compassion. That is lovingkindness, a necessary accompaniment to compassion, but not compassion itself. Compassion is to enter into the pain of the other as a mother would enter into the pain of her child, and only after that does lovingkindness fulfill its role of attempting to ease that understood pain.

In light of true spiritual community, this makes complete sense. If we are one through God, then we should feel the pain of those around us as acutely as if it were our very own. We have an obligation not only to provide comfort, but also to look on our fellow man with the mother-love of compassion and be moved with the heart of God to understand their pain as our own.

Photo Credit: DWilliams/bridgesforpeace.com

Zechariah 7:9 exhorts us to “execute true justice, show mercy and compassion everyone to his brother.” It is specifically against this exhortation that Israel disobeyed, leading to the scattering of the people amongst the nations. Before the Lord leveled this punishment, however, He explained that the lack of justice, compassion, and mercy came because the people “stopped their ears so they could not hear” and “made their hearts like flint” (Zech. 7:11b,12a). Here lack of compassion is associated with not only refusing to listen to the law of the Lord, but also with closed ears and hardened hearts.

Compassion, to enter into the sorrow or pain of another person, cannot happen if the compassionate refuse to soften their hearts or open their ears. Proverbs 28:27 confirms the link between looking away from the needy and exhibiting a lack of compassion and lovingkindness: “He who gives to the poor will not lack, but he who hides his eyes will have many curses.”

So let us not hide our eyes. We have been given the gift of community through the Body of Christ––we must not waste it.

Kaplan, Mordecai M. Basic Values in Jewish Tradition. New York: Craftsman Associates, Inc., 1948.

Pearl, Dr. Chaim, Ed. The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life and Thought. Jerusalem: Carta, The Israel

Map and Publishing Company, Ltd., 1996.

Sears, David. Compassion for Humanity in the Jewish Tradition. New Jersey: Jason Aronson Inc.,

1998.

Steinberg, Milton. Basic Judaism. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers, 1947.

All Scripture is taken from the NKJV.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.