×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Rev. Peter J. Fast, Deputy National Director, Canada

The book of Ezra resounds with the crucial concept and powerful truth of restoration. The Hebrew word for “restore” is shuv, which means to return to a prior state, restore to a former condition or turn back. It may entail the actual physical action of turning or refer to spiritually turning from evil to God. The spiritual connotation puts the emphasis on the right motivation of turning from sin, namely to turn back to the Lord. God thus takes His rightful place as the focal point of shuv and sin does not steal center stage. Wilson’s Old Testament Word Studies explains the “conversion or turning to God” as “a re-turning or a turning back again to Him from whom sin has separated us, but whose we are by virtue of creation, preservation and redemption.”

The book of Ezra resounds with the crucial concept and powerful truth of restoration. The Hebrew word for “restore” is shuv, which means to return to a prior state, restore to a former condition or turn back. It may entail the actual physical action of turning or refer to spiritually turning from evil to God. The spiritual connotation puts the emphasis on the right motivation of turning from sin, namely to turn back to the Lord. God thus takes His rightful place as the focal point of shuv and sin does not steal center stage. Wilson’s Old Testament Word Studies explains the “conversion or turning to God” as “a re-turning or a turning back again to Him from whom sin has separated us, but whose we are by virtue of creation, preservation and redemption.”

Restoration is central in the book and life of Ezra, both in a physical reality as the Jewish people return to the Land of Israel, and in a spiritual reality as they repent and turn back to God. Three key themes emerge from this central idea: restoration of the land, restoration of the people and restoration of the Bible. We see the restoration of God’s love, mercy, will and covenantal nature across the three themes.

Interestingly, these same three themes have emerged in the restoration of the modern State of Israel in the 20th century, with the restoration in Ezra’s day mirrored in the rebirth of the Jewish state thousands of years later.

Before plunging into the world of Ezra, let’s examine another concept tied to restoration. Faithfulness, or emunah in Hebrew, expresses God’s unending faithfulness to the Abrahamic covenant (Gen. 17, Ps. 105:7–11) that underpins His relationship with the Jewish people and the continued existence of Israel. It is also His great faithfulness that gave birth to the Church on Pentecost (Acts 2) in the first century. The Church, a wild olive shoot God faithfully grafted into the olive tree that is Israel, was not to replace Israel. Instead, it was to receive life, support and nourishment from the Abrahamic covenantal root, as the apostle Paul explained in Romans 11. “I say then, has God cast away His people? Certainly not! …God has not cast away His people whom He foreknew” (vv. 11:1a, 2a).

That faithfulness is clearly seen as we trace the history of the Jewish people through very difficult times. The Bible records the devastation wrought upon the kingdom of Judah and Jerusalem by the armies of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon (2 Kings 24–25, 2 Chron. 36) in 586 BC. The Babylonians destroyed Solomon’s Temple and slaughtered a great multitude. After the destruction, hundreds of thousands of people—the cream of the crop of Jewish society—were taken into exile to Babylon, over 750 miles (1,207 km) to the east. Only poor Jewish peasants remained in the Land and were barely able to survive.

Yet well before the devastation, God revealed to Jeremiah that Babylon would come in judgment because of Judah’s wickedness. He recorded the prophecies to Judah concerning the threat in the book of Jeremiah. “And this whole land shall be a desolation and an astonishment, and these nations shall serve the king of Babylon seventy years” (25:11). Yet the distressing report was tempered with hope. “For thus says the LORD: After seventy years are completed at Babylon, I will visit you and perform My good word toward you, and cause you to return to this place” (29:10). One hundred and fifty years earlier, Isaiah had also prophesied concerning Judah’s future restoration, even naming the king whom God would use to restore the Jewish people to the Land to rebuild the Temple. “Who says of Cyrus, ‘He is My shepherd, and he shall perform all My pleasure, saying to Jerusalem, “You shall be built,” and to the temple, “Your foundation shall be laid””’ (Isa. 44:28).

Room 55 of the British Museum in London, England is home to the “Cyrus Cylinder.” The baked clay cylinder dates back to the sixth century BC and bears a message written in the Akkadian cuneiform script. This ancient document was issued by Cyrus the Great of Persia in the year 539 BC after he captured the city of Babylon from Nabonidus, the king of Babylon and the father of Belshazzar, ending the Neo-Babylonian Empire (Daniel 5–6).

After the dust of conquest had settled, Cyrus extended liberties to the exiled Jews of Judah, decreeing their freedom in fulfillment of the prophecies of the God of Israel. The hope of the exiled Jews in His divine promises was made a reality after 70 years of exile. Matthew Barrett explains in None Greater: The Undomesticated Attributes of God that the fulfillment of the promise was based on God’s faithfulness, which is intrinsic to His nature. “He does not change in who He is (His essence); therefore He does not change in what He says and does (His will). He will not go back on His covenant promises to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob [see Mal. 3:6]. Yes, Israel has been unfaithful to the covenant, but the Lord has been and will remain faithful.”

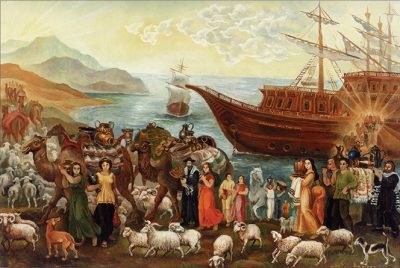

The book of Ezra immerses us in the complexities of this challenging time in history. The Jews had returned to find their homeland desolate. Though restoration had begun, tough times lay ahead. Ezra 1:1 takes a backward look at history and recalls the time when Cyrus first issued his decree that the Jews could return to Israel. Seventy years had gone by since the proclamation that would open the door for nearly 43,000 exiles to return to Jerusalem under the leadership of Zerubbabel. “Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of the LORD by the mouth of Jeremiah might be fulfilled, the LORD stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia, so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom, and also put it in writing…” (see also 2 Chron. 36:22–23).

The book of Ezra immerses us in the complexities of this challenging time in history. The Jews had returned to find their homeland desolate. Though restoration had begun, tough times lay ahead. Ezra 1:1 takes a backward look at history and recalls the time when Cyrus first issued his decree that the Jews could return to Israel. Seventy years had gone by since the proclamation that would open the door for nearly 43,000 exiles to return to Jerusalem under the leadership of Zerubbabel. “Now in the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, that the word of the LORD by the mouth of Jeremiah might be fulfilled, the LORD stirred up the spirit of Cyrus king of Persia, so that he made a proclamation throughout all his kingdom, and also put it in writing…” (see also 2 Chron. 36:22–23).

The first order of business would be to rebuild the Temple, followed by the physical restoration of the cities and the land. The Land of Israel had paid a heavy price during the Babylonian invasion. It was common practice in battles of old for armies to destroy agriculture to deprive their enemies of food, fell trees to sever the supply line for weapons of war, decimate roads and infrastructure, tear up the landscape, burn cities and deplete both the human and livestock populations. Through these scorched-earth policies, an invading army could lay waste to a once rich and prosperous land. The exiles returning to Judea thus had to restore the land, plant crops and trees, rebuild homes and cities and raise up defenses. Yet they could not do this on their own and looked to God for favor and blessing.

By the time Ezra arrived in Jerusalem (Ezra 7), the people had become fearful and had lost heart and sight of their vision as their surrounding enemies constantly threatened and intimidated them. He was shocked to see the city unprotected and still badly in need of restoration, despite decades having passed since the days of Zerubbabel. This was the same agony Nehemiah felt when he heard that Jerusalem’s walls were still in ruins (Neh. 1:3). God ignited a fire in Nehemiah’s heart and made it possible for him to receive permission from King Artaxerxes to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the walls in a mere 52 days (Neh. 6:15).

Thousands of years later, the Jewish people would again return to the land of their forefathers after nearly two millennia of dispersion in the Diaspora. In the late 19th century, decades before the birth of the modern State of Israel, they found their homeland in much the same condition as in the days of Zerubbabel. It had been abused for four centuries by Turkish rule, laid to waste and was underdeveloped, lacking trees and proper soil for agriculture and full of malaria-ridden swamps. As Mark Twain stated in 1869 in The Innocents Abroad, “Nowhere in all the waste around was there a foot of shade, and we were scorching to death…this blistering, naked, treeless land.” Leading soil conservationist Walter Clay Lowdermilk wrote in 1938, “The Holy Land can be reclaimed from the desolation of long neglect and wastage and provide farms, industry, and security for possibly five million Jewish refugees…It had gone from being ‘a land flowing with milk and honey’ to a land of desolation” (see Deut. 29:22–29). Yet these incredible Jewish pioneers—like their ancient ancestors—began to transform the land into a Garden of Eden. This is the modern-day miracle visible to anyone traveling the Land of Israel in the 21st century.

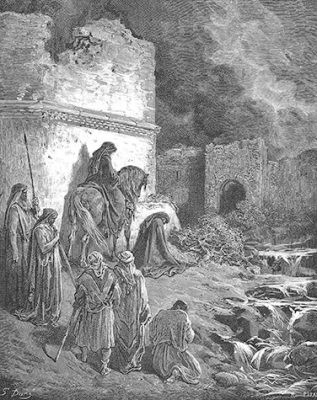

Ezra 1:1–4:5 recounts the first wave of exiles returning to Jerusalem and rebuilding the altar to the Lord in the place of the Temple ruins. We read that the “priests and Levites and heads of the fathers’ houses” who were old men remembered the splendor of the First Temple and “wept with a loud voice when the foundation of this temple was laid before their eyes” (Ezra 3:12) At the same time, “many shouted aloud for joy.” This reveals the juxtaposition of the people’s reactions (Hag. 2:3). For the younger Jewish people born during the exile, there was no memory of the First Temple. Seeing the altar restored before them was thus cause to celebrate. God’s restoration was at hand. Yet for the older generation, it was bittersweet—a reminder of the former glory that had been Solomon’s Temple.

Ezra 1:1–4:5 recounts the first wave of exiles returning to Jerusalem and rebuilding the altar to the Lord in the place of the Temple ruins. We read that the “priests and Levites and heads of the fathers’ houses” who were old men remembered the splendor of the First Temple and “wept with a loud voice when the foundation of this temple was laid before their eyes” (Ezra 3:12) At the same time, “many shouted aloud for joy.” This reveals the juxtaposition of the people’s reactions (Hag. 2:3). For the younger Jewish people born during the exile, there was no memory of the First Temple. Seeing the altar restored before them was thus cause to celebrate. God’s restoration was at hand. Yet for the older generation, it was bittersweet—a reminder of the former glory that had been Solomon’s Temple.

The returning exiles came under increasing pressure from supposed well intentioned neighbors. These surrounding tribes initially offered to worship with the Jews. When Zerubbabel declined, they quickly became “adversaries of Judah” (Ezra 4:1). The foreign tribes afflicting the Jewish people were installed in Samaria by Assyrian King Sennacherib (2 Kings 17:24–41) and later became known as Samaritans (John 4:19–22). They claimed to have worshiped and sought after the God of Israel since the days of Esar-Haddon (Ezra 4:2, 2 Kings 19:37), Sennacherib’s son and successor. In truth, these Samaritans had adopted a distorted version of the Jewish faith, sacrificing to the God of Israel as well as to their own idols.

After giving some background on their many troubles, Ezra diverts from his account of the Temple and moves forward in time to focus on threats during the reconstruction period of the city walls as outlined in the book of Nehemiah. Ezra records that these enemies of Israel spread lies about the nature of the reconstruction and sent letters to discredit the Jews to the Persian kings. Israel’s enemies during Nehemiah’s time had a simple plan: make the Jews look like rebels of Persia, undermining the earlier wishes of Cyrus the Great and halting the rebuilding of the walls. While the efforts by Israel’s enemies were eventually proven false, the interruptions meant that building only resumed by the second year of King Darius I’s reign.

In Ezra 5–6, the account turns back to the Temple with prophets Haggai and Zechariah prophesying and inspiring the people to complete the Temple. “And they built and finished it, according to the commandment of the God of Israel, and according to the command of Cyrus, Darius, and Artaxerxes king of Persia” (Ezra 6:14b). The Temple was finished on the third day of Adar in the sixth year of King Darius’s reign (6:15). God’s word to Isaiah given over 200 years earlier had been fulfilled. The people dedicated the restored Temple with sacrifices (6:16–18) and celebrated Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread (vv. 19–22) on the 14th day of the first month (see Exod. 12:3–10; Deut. 16:1–3).

Ezra knew the people would have to be willing to humble themselves and dedicate themselves to the Lord in order for true restoration to occur. God chose him, a man described as a “priest,” “scribe,” “expert in the words of the commandments of the Lord, and of His statutes to Israel” (Ezra 7:11) because he would lead the people by example and teach them to cherish the Word and the commandments of the Lord. King Artaxerxes knew Ezra as “a scribe of the Law of the God of heaven” (v. 12), a testimony to the impact and influence Ezra wielded in the courts of Babylon. He had God’s favor in departing from Babylon (7:9, 8:1–36) and carried a letter of support from King Artaxerxes (7:13–26).

Ezra was a man God chose to breathe life into a people struggling in their restoration. Judaism places Ezra in a highly esteemed place in the Men of the Great Assembly. According to Rabbi Binyamin Lau, “Ezra’s governorship and that of Nehemiah which followed soon after, mark the beginning of what we know as the period of the ‘Men of the Great Assembly.’ The last of the prophets—Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi—all belong to this period of the Return to Zion.”

The Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers—commentary of the Mishnah (first written recording of Jewish tradition) that discusses the Torah’s (Gen.–Deut.) position on ethics and interpersonal relationships) also includes a fascinating statement showing Ezra’s responsibility among other giants of faith. “Moses received Torah from Sinai, and passed it on to Joshua, and Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets passed it on to Men of the Great Assembly” (1:1A).

When Ezra returned to Jerusalem, he was prepared to confront issues of sin among the people—not by his own strength, but by the strength of the living God. Sin had gone unchecked, and many of the people—even priests and Levites—had married idolatrous, foreign women (Ezra 9), contravening God’s commandments (see Deut. 7:2–5, Josh. 23:11–13). Ezra faced this head-on by grieving, fasting and praying for the people (9:3–15, 10:1) to return (shuv) to the Lord. He listened to the repentant leaders (10:2–4) and issued disciplinary action (10:5), which led to the people divorcing their pagan wives and repenting.

In Ezra’s time, all the books comprising the Tanakh (OT) had not been written yet. His Bible would have included the first five books of Moses and other Scriptures he had access to, such as the Writings and some of the Prophets. I believe the word “Bible” should communicate to us the concept of the entire Scriptures and the Word of God. Ezra arguably carried the same convictions.

In Ezra’s time, all the books comprising the Tanakh (OT) had not been written yet. His Bible would have included the first five books of Moses and other Scriptures he had access to, such as the Writings and some of the Prophets. I believe the word “Bible” should communicate to us the concept of the entire Scriptures and the Word of God. Ezra arguably carried the same convictions.

The Jewish people hail Ezra as a model of biblical stewardship. The Talmud (rabbinic commentary on Jewish tradition and the Hebrew Scriptures) describes him “as worthy of having received the Torah, had not Moses preceded him.” Ezra was a scribe and an expert on Torah (Gen.–Deut.). He taught the people and brought them back to God’s Word as the lifeblood coursing through their veins, as shown in Nehemiah 8:5–6: “And Ezra opened the book in the sight of all the people, for he was standing above all the people; and when he opened it, all the people stood up. And Ezra blessed the LORD, the great God. Then all the people answered, ‘Amen, Amen!’ while lifting up their hands. And they bowed their heads and worshiped the LORD with their faces to the ground.”

The reaction of the people is phenomenal. Nehemiah 8:9 gives us another glimpse: “And Nehemiah, who was the governor, Ezra the priest and scribe, and the Levites who taught the people said to all the people, ‘This day is holy to the LORD your God; do not mourn nor weep.’ For all the people wept, when they heard the words of the Law.”

Ezra is considered one of the supreme teachers in Jewish history. Rabbi Nosson Scherman summarizes the prominence ascribed to Ezra in The Stone Edition: TANACH, “He and the Men of the Great Assembly returned the crown of God’s greatness to its former splendor by teaching successive generations to seek His beneficent hand behind the mists of history and the ephemeral ascendancy of the wicked. That teaching will illuminate the universe when the final Redemption is at hand.”

We should take these examples of worship, repentance and emotional brokenness seriously in an age when biblical illiteracy is rampant in the Church. God’s Word is an anchor in a world that frequently seems to spin out of control. His Word holds us firm, directs us to Him, calms our hearts and shows us His will—and just as in the days of Ezra, He remains faithful to restore.

Barrett, Matthew. None Greater: The Undomesticated Attributes of God. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2019.

Ben Yehudah, Mme., Fullerton, Kemper and contributors. Jerusalem: Its Redemption and Future: The Great Drama of Deliverance Described by Eyewitnesses. New York: The Christian Herald, 1918.

Berkson, William. Pirke Avot: Timeless Wisdom for Modern Life. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2010.

Brown, Francis, Driver, S.R. & Briggs, Charles A. The New Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius Hebrew and English Lexicon. Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1979.

Evans, Mike. The Visionaries. Phoenix: Time Worthy Books, 2017.

Green, Jay P. Sr., (ed.). The Interlinear Bible: Hebrew-Greek-English. United States of America: Hendrickson Publishers, 2012.

Lau, Binyamin. The Sages: Character, Context & Creativity: Volume I: The Second Temple Period. Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2010.

Packer, J.I. & M.C. Tenny, (ed.). Illustrated Manners and Customs of the Bible. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1980.

Scherman, Nosson, (ed.). The Stone Edition: TANACH. Brooklyn: The ArtScroll Series Mesorah Publications Ltd.: New York, 2010.

Strong, James. The New Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2001.

Twain, Mark. The Innocents Abroad. Signet Classics. Printed in the United States of America. 2007.

Wilson, William. Wilson’s Old Testament Word Studies. McLean: Macdonald Publishing Co., 1990.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.