by: Kathy DeGagne, BFP Staff Writer

Photo: danm12/ Shutterstock.com

The Spice and Incense Route—those words conjure images of long camel caravans ferrying trade goods across the Negev desert to Jerusalem and points beyond.

On this exotic desert road connecting the Orient with the Roman Empire, the precious commodities of frankincense and myrrh were transported over vast distances to satisfy the insatiable Roman appetite for spices, perfumes and incense.

We first discover the ancient beginnings of the spice route in the biblical story of Joseph when his brothers sold him to a caravan of Ishmaelite traders on their way to Egypt (Gen. 37:25). The camel caravan, laden with spices, balm and myrrh, came from Gilead, a region in northern Israel famed for its medicines. The Queen of Sheba also paved the way for a spice route from Africa on her way to visit Solomon in Jerusalem, bringing with her a great retinue and untold wealth in spices, gold and precious stones (1 Kings 10:2).

In the 1st millennium BC, burning incense to the gods became a significant pagan practice throughout the Mediterranean. As the demand for frankincense soared, so did prices. Incense and other precious spices were also used in Jewish Tabernacle and Temple ritual. The Lord dictated His special incense recipe to Moses; it was to be made of equal parts “fragrant spices, gum resin, onycha and galbanum—and pure frankincense” (Exod. 30:34 NIV).

Trade goods from the Orient came by ship to ports in Yemen. Frankincense was the main commodity, but cargoes also included Arabian balsam for medicine; myrrh for perfumes, cosmetics and embalming; labdanum for perfumes; Oriental spices such as pepper, cinnamon, cassia and cardamom; herbs, African wood, pearls, Indian silks and metals. At Yemen they were loaded onto the camel trains, transported across Saudi Arabia and Jordan, then through Israel to the prosperous terminal port of Gaza on the Mediterranean Sea, an overland journey of 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles). At Gaza, the goods were loaded onto ships bound for markets all over the Roman Empire.

Because of its location, Israel was at the crossroads of culture and religion for millennia. The Spice and Incense Route provided a way to transport trade goods, but it also allowed access for people and the exchange of ideas from one end of the known world to the other.

Photo: Eric Gaba (Sting – fr:Sting)/ Wikipedia

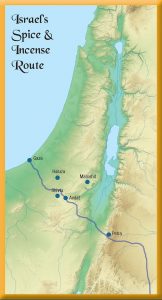

When the Spice and Incense Route entered the borders of Israel, it stretched 150 kilometers (93 miles) from Moa on the Jordanian border to Gaza, with way stations (caravanserai) set at one-day intervals. The ancient ruins of Avdat, Haluza, Mamshit and Shivta, where caravans, a thousand strong, would rest and water their camels, give testament to the active spice trade that flourished in the Negev for centuries.

The caravan merchants became extremely wealthy as middlemen in this huge trade network. These were the Nabateans, a nomadic Arab tribe that rose to prominence in the spice trade during the 3rd century BC and then mysteriously disappeared in the 4th century AD. For hundreds of years, they were masters of the desert, familiar with the best routes to travel through an inhospitable land, developing a network of roads, forts, cities and caravanserais to support the lucrative trade routes.

They chose near-impassable routes to confound highway bandits and protect their valuable cargoes, establishing military forts at critical intervals. They knew where all the natural watering holes were, but they also developed advanced damming systems, channels and reservoirs for collecting and preserving rain and floodwater. They built secret cisterns along the route, undetectable by others, but large enough to water entire caravans many times over. They understood that water was a more precious commodity than the enormous wealth they traded in. With that insight alone, they dominated the spice trade for centuries.

Petra was the halfway mark between Yemen and Gaza and served as the Nabatean capital. Because of their nomadic lifestyle, Petra became a spectacular site to bury their dead rather than a place to live. The Nabateans eventually left their nomadic life and put down roots, becoming herders of sheep, cattle and goats, domesticating wild camels for use in the caravans and planting vineyards.

In an attempt to tap into the lucrative spice trade, the Greco–Romans learned how to sail a direct route from Egypt through the Red Sea to southern Arabia and India, gradually rendering the overland route superfluous, and drawing the golden age of the Nabateans and Israel’s Spice Route to a close.

In the Tanakh, the Song of Songs offers this poetic image of the ancient spice trade: “Who is this coming up from the wilderness like a column of smoke, perfumed with myrrh and incense made from all the spices of the merchant” (3:6 NIV). Yet, here in Israel, the past, present and future often collide. Isaiah 60 gives us a prophetic picture of the wealth of the nations streaming to Israel on camel caravans in the Kingdom Age. “The multitude of camels shall cover your land…they shall bring gold and incense and they shall proclaim the praise of the LORD” (v. 6).

Traveling through the Negev wilderness, unchanged for millennia, the landscape dotted by tenacious tamarisk trees, chalk cliffs and ibex, it’s not hard to imagine endless colorful caravans still journeying across its rocky face, the fabled Spice Route forever etched into the fascinating lore of this ancient land called Israel.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.