by: Cheryl Hauer, International Vice President

The global media has its eagle eye continually focused on the Jewish state. Its Knesset (Parliament) and the legislative branch of the government, the prime minister and the executive branch, the Israel Defense Forces and Israel’s security forces—to name a few—all take their turns under the microscope. And the international community is never short on opinions. This time, it’s Israel’s judiciary that is making headlines around the world. In the face of suggested changes to the judicial branch by the Netanyahu coalition, everyone from US President Biden to French President Macron and leaders of the European Union (EU) are weighing in on exactly what Israel should and shouldn’t do.

The global media has its eagle eye continually focused on the Jewish state. Its Knesset (Parliament) and the legislative branch of the government, the prime minister and the executive branch, the Israel Defense Forces and Israel’s security forces—to name a few—all take their turns under the microscope. And the international community is never short on opinions. This time, it’s Israel’s judiciary that is making headlines around the world. In the face of suggested changes to the judicial branch by the Netanyahu coalition, everyone from US President Biden to French President Macron and leaders of the European Union (EU) are weighing in on exactly what Israel should and shouldn’t do.

A recent Jerusalem Post article referring to this controversy mentioned the book of Ruth that begins with the interesting comment, “In the days when the judges ruled, there was a famine in the land” (1:1). The author does admit that the Bible insinuates no actual cause and effect between the two, but perhaps it does intimate Israel’s difficult history under the leadership of judges. Of course, when Ruth and Boaz walked the land, Israel was not a democracy. A lot has changed, and it seems more change may be on the horizon.

So the logical questions might be, “What is all the excitement about? What are these changes and how would they affect the country?” These can only be answered by taking a quick look at Israel’s judiciary and how it functions.

Israel is a parliamentary democracy with an independent judiciary headed by a Supreme Court. Also known as the Higher Court of Justice, it currently consists of fifteen judges, a number that is established by the Knesset and has varied over the years. The position of president of the court is held by the most senior justice, while the second most senior justice becomes the deputy president. All Israeli judges, including those on the Supreme Court, are appointed by a selection committee that consists of three Supreme Court judges, including the president, two cabinet members, including the Minister of Justice, two Knesset members and two representatives of the Israeli Bar Association. This process differs significantly from other courts like the EU Court of Justice, where justices are appointed at the the consent of all member states, or the US, where Supreme Court justices are presidential appointees requiring Congressional approval and where lower court judges are elected.

As in other countries with similar systems, Israel’s Supreme Court is tasked with maintaining the rule of law and protecting individual rights. However, because Israel has no written constitution or bill of rights, the court functions somewhat differently than its international counterparts. In the US, for instance, the Supreme Court only hears already existing cases where there is controversy and which a party to the case brings to the court. Israel has no such restrictions. Although the Supreme Court has jurisdiction to hear criminal and civil appeals from lower courts, it can also hear other matters with the Court’s permission. These could include matters regarding Knesset elections, rulings of the Civil Service Commission, disciplinary rulings of the Israeli Bar Association, administrative detentions and other matters not based on existing lower court cases.

The system also includes District Courts that have jurisdiction in any matter not specifically under the jurisdiction of another court. These courts handle some criminal and civil matters and are the appellate court for the Magistrate Courts. Magistrate Courts are the country’s basic trial courts that handle criminal, civil and real estate matters. Since there are no jury trials in Israel, each case is heard by a lone decision-maker. The legal system also recognizes tribunals, which are independent courts with their own appellate systems and include military, labor and religious courts. Administrative tribunals are designed to deal with specific legal issues. One such tribunal deals with social benefits and compensation from injury, while a second handles unfair terms in contracts and a third rules on a range of uncompetitive business practices.

All of these courts are under the supervision of the High Court of Justice. As such, the court also exercises judicial review of the other branches of government. The court hears over 1,000 petitions every year, many of them high profile cases challenging the actions of top government officials. This court may also challenge the decision of a Supreme Court three-judge panel and order it retried under a five-judge panel. And within the system, all judges have a very high degree of independence. Their appointment is permanent, and Israel’s Basic Law states that any person in whom judicial power is vested will, in judicial matters, be “subject to no authority but that of the law.” A judge is required to retire at 70, which is older than in other sectors, and can only be removed from office by a decision of the Court of Discipline where seven of its nine members must approve the removal.

The controversy that is garnering so much international attention stems from a proposal made by Justice Minister Yariv Levin that would transfer some of the power now held by the judicial branch of the government to the legislative and executive branches. It would grant the government more control over the appointment of judges by including more political figures on the selection committee. In addition, it would allow the Knesset to re-legislate laws that the court has struck down with only a majority of 61 votes of Knesset’s 120 members. Levin claims that power which belongs to elected officials now lies in the hands of overly interventionist judges. “We go to the polls and vote,” he recently said, “but time after time, people we didn’t elect decide for us.” Levin claims that’s not democracy. Many others disagree with him, however, and the battle lines have been drawn, with the international community making sure their voices are heard as well. Clearly, however, the definition of Israeli democracy is what hangs in the balance.

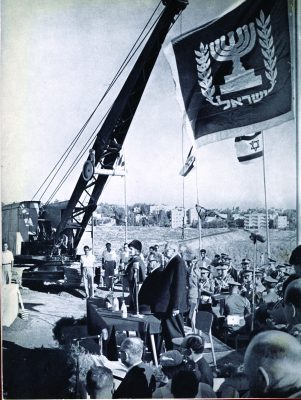

Photo Credit: Click on photo to see photo credit

Photo License: Maats Knesset Cornerstone Jerusalem 1958

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.