by: Cheryl Hauer, Vice President

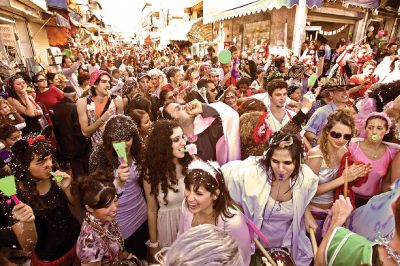

On March 20–21, the Jewish community worldwide will enjoy one of the happiest festivals in their yearly cycle. Today, the holiday known as Purim (Feast of Esther) is celebrated by increasing numbers of Christians as well. It’s a time of frivolity, dressing in costumes, giving gifts of food to the needy and lots of boisterous and exuberant partying. The celebration, as commanded in the book of Esther, commemorates the deliverance of the Jewish people in Persia from a nearly successful plan to destroy them completely. Were it not for the courage of Mordechai and his niece, Queen Esther, the plot of evil Haman would have succeeded and thousands of Jewish people—some experts believe as much as 20% of the population of Persia at the time—would have been slaughtered.

On March 20–21, the Jewish community worldwide will enjoy one of the happiest festivals in their yearly cycle. Today, the holiday known as Purim (Feast of Esther) is celebrated by increasing numbers of Christians as well. It’s a time of frivolity, dressing in costumes, giving gifts of food to the needy and lots of boisterous and exuberant partying. The celebration, as commanded in the book of Esther, commemorates the deliverance of the Jewish people in Persia from a nearly successful plan to destroy them completely. Were it not for the courage of Mordechai and his niece, Queen Esther, the plot of evil Haman would have succeeded and thousands of Jewish people—some experts believe as much as 20% of the population of Persia at the time—would have been slaughtered.

On the surface, it is a beautiful story. Countless movies, books and even cartoons have been created to share the rags-to-riches saga of poor but beautiful Jewish Hadassah, who wins the heart of the king and becomes Esther, Queen of all Persia. Few of them, however, bear much of a resemblance to the story as it is recounted in the Bible. In reality, this was no fairy tale. It’s the account of a violent period in the history of the Jewish people, when young girls were torn by force from their families and the Persian Jews were forced to defend themselves against a decree of genocide.

Israel’s life in the Diaspora began in 722 BC when the Northern Kingdom fell to the Assyrians. As a strategy, these conquerors forced newly subjugated people to migrate in large numbers to other areas of the empire. The region was, therefore, a melting pot of diverse cultures, religions and languages, or as the Jewish Virtual Library calls it, “a vast experiment in cultural mixing.” It was the Assyrian monarch, Sargon II, who forcefully relocated the Jews from Israel, allowing them to establish Jewish infrastructure, create Jewish cities and communities, build Jewish schools and live in relative peace and comfort. By the time the Southern Kingdom was conquered by Babylon and Israel’s brightest and best were exiled to the same region, now under Babylonian control, a secure community with a strong sense of Jewish identity awaited them.

Israel’s life in the Diaspora began in 722 BC when the Northern Kingdom fell to the Assyrians. As a strategy, these conquerors forced newly subjugated people to migrate in large numbers to other areas of the empire. The region was, therefore, a melting pot of diverse cultures, religions and languages, or as the Jewish Virtual Library calls it, “a vast experiment in cultural mixing.” It was the Assyrian monarch, Sargon II, who forcefully relocated the Jews from Israel, allowing them to establish Jewish infrastructure, create Jewish cities and communities, build Jewish schools and live in relative peace and comfort. By the time the Southern Kingdom was conquered by Babylon and Israel’s brightest and best were exiled to the same region, now under Babylonian control, a secure community with a strong sense of Jewish identity awaited them.

Seventy years later, when the Babylonians fell to the Persians and the Jewish people were permitted to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the walls of the city, the vast majority chose to stay in Babylon under Persian domination. It is estimated that there were a million or more Jews living in the Persian Empire at that time, of which only 42,000 returned to Israel. The Diaspora community flourished as a center of Jewish learning and spirituality. Persian leaders respected Jewish laws and customs and allowed Jewish leaders a degree of autonomy within their communities. Their treatment of the Jewish people was so appreciated that the Talmud (rabbinic commentary on Jewish tradition and the Hebrew Scriptures) says a picture of Susa (the capital of the Persian Empire, also called Shushan) should be carved on the eastern gate of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Most scholars today believe that King Ahasuerus, who made Esther his queen, was in fact Artaxerxes I. Some also believe that by this time, a degree of anti-Semitism had crept into Persian society. Mordechai was careful to instruct Hadassah to keep her Jewishness a secret, they remind us, and the king seemed quick to agree with Haman that the entire Jewish population of Persia, including women and children, should be killed. The Jewish people were also obviously unable to defend themselves until the king decreed it. Even under those circumstances, however, it is hard to imagine the horror and disbelief that fell upon the Persian Jews when they were told a decree calling for their destruction would be implemented in just a few days. Much like in World War II Europe, Jewish parents would have tried desperately to save their children. They would have frantically sought some route of escape and offered urgent prayers. The actions of Mordechai and Esther would bring last minute deliverance to a terrified community.

Deliverance didn’t come in the form of a decree making the threat null and void. Instead, the Jews were allowed to defend themselves against those who would kill them. The battle ensued, and nearly 80,000 enemies of the Jews were killed throughout the empire. There is no record of how many Jewish people lost their lives. It seems both communities would have been devastated by this horrific event, leaving the land soaked with blood and the empire in mourning. Yet in response, Queen Esther and Mordechai, with the king’s authority, proclaimed Purim to be a holiday of feasting and joy for all generations.

Deliverance didn’t come in the form of a decree making the threat null and void. Instead, the Jews were allowed to defend themselves against those who would kill them. The battle ensued, and nearly 80,000 enemies of the Jews were killed throughout the empire. There is no record of how many Jewish people lost their lives. It seems both communities would have been devastated by this horrific event, leaving the land soaked with blood and the empire in mourning. Yet in response, Queen Esther and Mordechai, with the king’s authority, proclaimed Purim to be a holiday of feasting and joy for all generations.

Today, the Jewish people face another decree of genocide. Enemies much more powerful than those of the ancient Persian empire await the opportunity to destroy the people of Israel—every man, woman and child—many of whom have already faced a similar decree of genocide that we know as the Holocaust. Yet on March 20–21, the Jewish people will rejoice. They will sing and dance in the streets, dress their children in costumes and take plates of food to their neighbors. The entire country will be alive with celebration. It seems counterintuitive.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks explains it this way:

“That is what we do on Purim. The joy, the merrymaking, the food, the drink, the whole carnival atmosphere, are there to allow us to live with the risks of being Jewish—in the past and tragically in the present also—without being terrified, traumatized or intimidated. It is the most counterintuitive response to terror and the most effective. Terrorists aim to terrify. To be a Jew is to refuse to be terrified. The people that can know the full darkness of such history and yet rejoice, is a people whose spirit no power on earth can ever break.”

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.