by: Cheryl Hauer, Vice President

The onset of April means spring in the northern hemisphere and autumn south of the equator. Both are marked by changes in temperature, foliage and even activities, as the north warms up and the south cools down. There are, however, some things that remain constant no matter where you are on the globe, and one of them is the biblical festival called Pesach (Passover).

The onset of April means spring in the northern hemisphere and autumn south of the equator. Both are marked by changes in temperature, foliage and even activities, as the north warms up and the south cools down. There are, however, some things that remain constant no matter where you are on the globe, and one of them is the biblical festival called Pesach (Passover).

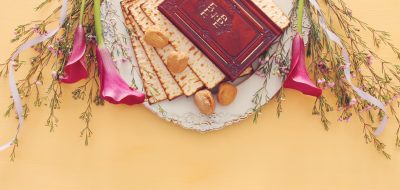

Celebrating the delivery of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery, Jewish communities the world over will begin their seven days of festivities on April 19 this year with a very special meal called a seder. Families will prepare their homes with the greatest care, setting tables with their finest and decorating with flowers, candles, ritual items and special foods. The tastiest of dishes will be prepared, and families will gather to remember the Exodus as though they themselves had been there when the Israelites began the journey that changed the course of human history.

For millennia, the basic elements of the Passover celebration have remained the same. The sacrificial lamb, bitter herbs, retelling the Exodus story and singing hymns have been part of the festivities from the time of Moses. However, things changed with the destruction of the Second Temple and the dispersion of much of the Jewish population. The home replaced the Temple as the center of Jewish life, and the biblical festivals changed as well. Jewish families throughout the world incorporated local foods and music and developed their own unique traditions to keep the story alive and relevant for each generation.

Take food for instance. Charoset is a delectable, thick salad—or in some communities a paste—that represents the mortar that the Israelites used in the construction of the pyramids. In Jewish homes of European descent, the mixture is made from apples, walnuts, cinnamon and red wine, while Mediterranean Jews mix citrus and dried fruits with almonds and white wine. The prize for unusual, however, goes to the Ethiopian and Yemenite communities, who actually thicken their charoset with the dust of real bricks.

Since the Bible links the eating of lamb to the Temple sacrifices, European Jews do not eat it at the seder, while Mediterranean Jews do. The Spanish Jewish community serves a delicacy called huevos haminados, which are eggs wrapped in onion skins and baked in the oven for 24 hours. Speaking of eggs, the ancient Yemenite community ate nothing but eggs at the seder: fried eggs, boiled eggs, baked eggs and egg salads. Fortunately, the menu expanded over the years and today the Yemenite fare is as sumptuous as any.

Preparation for the seder is an important element of the overall celebration, and every Jewish home is cleaned from stem to stern. All dust, dirt and especially chametz (leaven or yeast) are removed. Some families use a special small broom for getting into all the cracks, while others actually use a feather. Products containing leaven are gathered and once removed, some communities burn their chametz in special fires. Others actually give or sell it to their Gentile neighbors. In India, every Jewish home is not only cleaned, but also receives a fresh coat of paint every year.

Other unique traditions abound! In Ethiopian homes, the host dresses like an ancient traveler. Once all the guests are seated, he enters the home with a sack of matzot (plural for matzah, unleavened bread) slung over his shoulder. “Where are you coming from?” the family shouts. “Egypt,” he replies. “What are you carrying?” they query, and he replies by telling the story of the Exodus, beginning with the unleavened bread in his sack. As the story ends, the family asks, “And where are you going?” “Up to Jerusalem!” the traveler shouts, at which time dinner is served and the dancing and singing begin.

From Spain, Morocco, Turkey and Tunisia comes the interesting custom of tapping guests on the head with the seder plate. Once everyone is seated, the host circles the table, tapping each guest on the head once or twice as a reminder of life in Egypt where the Israelites carried their burdens on their heads. In Poland, buckets of water are thrown on the floor of the host’s home and guests wade through from one side of the room to the other, memorializing the parting of the Red Sea.

Perhaps the most interesting custom of all comes from the Jewish community originating in Afghanistan. A scallion or spring onion is given to every guest at the table. Each time the leader mentions slavery or bondage, participants hit their neighbor with the onion. The goal is to remind of the cruel bondage and mistreatment by the Egyptian slave masters, and it tends to be the favorite part of the seder for many. “It was the only time,” remarks one Afghani Jew, “when my mother told me it was alright to hit my brother!”

Of course, getting the children involved is critical, and today, traditions for that purpose continue to evolve. Some families toss popcorn to represent the plague of hail, while others sprinkle their guests with black rice reminiscent of lice. And naturally, there are the red stickers on arms and faces, reminding us all of that painful plague of boils.

Certain Passover customs have indeed evolved since the descendants of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob ate their first seder as soon-to-be-released slaves in Egypt—their feet shod and staff in hand, ready to depart for the Promised Land. Changing times and progressing generations do, after all, call for traditions to adapt to the times and seasons. Yesterday, the Passover sacrifice was one of the most important events in the calendar of the Holy Temple, with multitudes of worshipers pouring into the Temple courts to the sound of trumpets. Today, millions of the descendants of those multitudes gather around the seder table with the same heart of gratitude to remember God’s faithfulness. And tomorrow? Who knows how rituals and customs will evolve to adapt to the times and seasons of Jewish families. Yet despite the altering details from generations past to generations in the future, the essence remains unchanged. After all, it was God Himself who told the Jewish to mark the Passover as “a statute forever in your generations” (Lev. 23:41). Yesterday, today, tomorrow and for all perpetuity, Passover stands as a celebration of God’s mercy, compassion and faithfulness to show Himself mighty to save His people from the cruel yoke of slavery.

Photo Credit: tomertu/shutterstock.com

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.