by: Kathy DeGagne, BFP Staff Writer

Persian fallow deer (Photo: Shmuel Browns/israel-tourguide.info)

It was 1978 and the streets of Tehran echoed with the sounds of gunshots and wild mobs screaming, “Death to America! Death to Israel!” Iran was reeling under a volatile political inferno, soon to explode into the full-blown Islamic Revolution.

Trying to dodge angry demonstrators and stray bullets, a lone man hurried through the streets, intent on a secret mission—he was going to the zoo. The man was Israeli General Segev, the military attaché to Tehran, and his mission was to acquire and transport four Persian fallow deer from Iran to Israel as quickly as possible.

By the mid-20th century, the Persian fallow deer in Israel had been hunted to extinction and were thought to be extinct in the rest of the world as well. But then a small herd of 25 deer were discovered living in the forests of Iran. In 1962, the Israeli government decided to try and restore many of the endangered species no longer left in the biblical landscape, and one of the mandates of the newly-established Israel Nature and Parks Authority was to reintroduce the Persian fallow deer to Israel.

Nubian ibex (Photo: Shumel Brown/israel-tourguide.info)

Another Israeli general, Avraham Yoffe, founding member of the Haganah and director of the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, set out to curry favor with the Iranian political elite in a scheme to acquire some Persian fallow deer in exchange for Israel’s prized Nubian ibex. General Yoffe invited the shah’s brother, Prince Abdol Reza Pahlavi, and an Iranian wildlife official on two hunting trips to the Negev desert for Nubian ibex. In exchange for the privilege, the prince offered Israel four rare and precious fallow deer.

But time was of the essence—General Yoffe’s arrangement with the prince would break down as soon as the shah’s government collapsed.

On secret orders from General Yoffe, team member and Dutch zoologist Dr. Mike Van Grevenbroek, armed with a blow-dart gun disguised as a cane, tracked and captured four Persian fallow deer near the Caspian Sea. The deer were quickly loaded onto the last El Al flight out of Tehran, sharing the plane with Iranian Jews and Israeli diplomats fleeing the country.

Safely in Israel, the deer were transported to the Carmel Hai-Bar (literally “wildlife”) Nature Reserve, a breeding and reclamation center in northern Israel, where they flourished and multiplied. Fallow deer herds were successfully reintroduced into the wild in the Jerusalem Hills and the Galilee in 1996. Neot Kedumim (a biblical landscape reserve) and the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo also fostered deer herds.

Until World War I, the land of Israel was a veritable menagerie of Asian, African and European species, due to its location—at the crossroads of all three massive continents.

Hula painted frog (Photo: Mickey Sauni-Blank/wikipedia.org)

The pages of Scripture abound with references to a multitude of animals. Deuteronomy 14:4–5 speaks of the animals found in Israel which were acceptable to eat: ox, sheep, goat, fallow deer, gazelle, roebuck, wild goat, ibex, oryx, antelope and mountain sheep. Of those, only the ibex and gazelle survived into the mid-20th century. All the others, including the Syrian brown bear, Asian lion, Asian cheetah, and Nile crocodile, disappeared from the biblical landscape due to indiscriminate hunting and habitat destruction, primarily during the rule of the Ottomans.

One of the miraculous indicators of God’s covenant faithfulness to His people is that the Land of Israel is being restored to its former beauty and fruitfulness. The soil of Israel has again become rich and productive, and the animal life that once flourished here is being restored back to the Land. In Jeremiah 33:12, the Lord promised, “In this place, which is a wasteland without people or animals, and in all its cities, there will once again be pasture-lands where shepherds can let their flocks rest.”

Arabian Oryx (Photo: Charlesjsharp/ wikipedia.org)

It appears that, just as the Jewish people are returning to Israel from the countries of their dispersion, mammal and bird life seem to be making their way back to their ancestral homeland as well—some through human intervention such as conservation and habitat restoration, and others—all on their own.

In 2010, scientists were amazed by the sight of a grey whale swimming off the coast of Herzilya north of Tel Aviv. Grey whales became extinct in the Atlantic in the 18th century, and only inhabited the north Pacific. The sighting of a grey whale in the Mediterranean was the first sighting outside the Pacific in several hundred years. Another species, the Hula painted frog, disappeared from the Israel landscape in the 1950s, and was discovered in November 2011 after being gone over 50 years. In December 2011, a flock of singing swans landed in Israel after a 10-year hiatus.

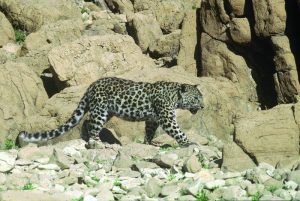

Arabian leopard (Photo: Yossi Od/wikipedia.org)

The establishment of over 190 nature reserves and 66 parks, which cover 20% of the country, has contributed to the strong comeback of many species. At the Yotvata Hai-Bar Nature Reserve, a rehabilitation center located in the Southern Negev, many endangered species indigenous to the Negev and Aravah regions are being brought back from the brink of extinction: the Somali wild ass, Arabian oryx, ostrich, onager, sand cat, Dorcas gazelle, Griffon vulture, Arabian wolf and Arabian leopard.

And true to form, Israel is sharing this blessing of wildlife rehabilitation with other nations. African countries such as Ghana and Senegal, attempting to revive indigenous species back to that continent, have received donations of Scimitar-horned oryx from Israel—just one of the many species now flourishing in Israel’s paradise restored.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.