by: Ilse Strauss, Assistant Editor

Each of the biblical feasts celebrated in Israel comes with its own set of Scriptural instructions, tried traditions and weird and wonderful customs. The Feast of Tabernacles signals seven joyous days of dwelling in temporary booths, and Purim (Feast of Esther) means dressing up in dazzling costumes. On Rosh HaShanah (Jewish New Year) the piercing call of countless ram’s horns resounds through the Promised Land, while Hanukkah (Feast of Dedication) is synonymous with candlelight, and Passover with matzah. Shavuot (Feast of Weeks) is no different.

Shavuot commemorates a watershed moment in Jewish history: God giving His instructions—the Torah (Gen.–Deut.)—to Israel at Mount Sinai some 3,300 years ago. Today, the descendants of those who stood around the shaking mountain mark the holiday by spending the evening wide awake, pouring over God’s instructions—a tradition of atonement born from the belief that Israel overslept on the morning of Shavuot and had to be roused by Moses to keep their appointment with God. After a night of Torah study, a throng of tired Jerusalemites wrapped in prayer shawls pour from synagogues, yeshivot (schools for religious studies) and front doors to flock to the Western Wall for prayers at dawn to thank God for the gift of His Torah. For dinner, family and friends gather for a feast of the best dairy treats Israel has to offer and dine on quiches, pastries, salads and cheesecake. Then, as another crucial Shavuot tradition, Israel reads the book of Ruth. Ruth? Why read about a Moabite widow on a holiday commemorating the events at Mount Sinai?

Ruth’s story is one of the most well-loved beauty-for-ashes tales in Scripture—and for good reason. A recently widowed Moabite princess turns her back on her people, gods, culture and country, and bids security, comfort and guaranteed plenty farewell to follow her Israelite mother-in-law into a future of uncertainty and barely enough with the now-famous words, “For wherever you go, I will go; and wherever you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God, my God” (Ruth 1:16).

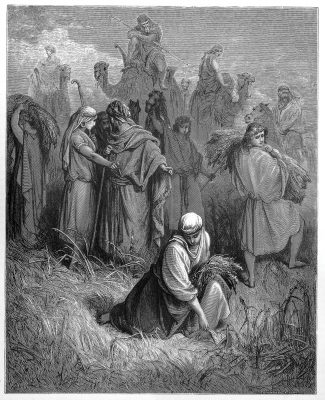

The impoverished pair arrives in Bethlehem during the barley harvest, where Ruth takes to the fields to glean leftover grain after the reapers. She catches the eye of well-to-do Boaz—in whose field she happens to glean and who happens to be her kinsman redeemer. Boaz marries Ruth, redeeming her and Naomi from uncertainty and barely enough to a future of security, comfort and guaranteed plenty. Naomi is blessed with a grandchild, and the widow from Moab becomes the great-grandmother of King David. Devastating tragedy. Epic romance. And a fierce, redeeming love. No wonder the story of Ruth is a firm favorite. Still, where is the connection between Ruth and Shavuot?

Shavuot, which means “weeks” in Hebrew, falls seven weeks, or 49 days, after Passover. The name is thus chronological, describing the time span between one festival to the next—and the close correlation between the two feasts. During the seven-week period, Israel progressed from a nation of former slaves delivered by the outstretched arm of God from the cruel oppression of Pharaoh—and the Angel of Death—to the foot of Mount Sinai, about to receive the Torah as the Almighty’s treasured possession 49 days later.

Shavuot, which means “weeks” in Hebrew, falls seven weeks, or 49 days, after Passover. The name is thus chronological, describing the time span between one festival to the next—and the close correlation between the two feasts. During the seven-week period, Israel progressed from a nation of former slaves delivered by the outstretched arm of God from the cruel oppression of Pharaoh—and the Angel of Death—to the foot of Mount Sinai, about to receive the Torah as the Almighty’s treasured possession 49 days later.

Both festivals also have an agricultural connection: Passover marks the beginning of the barley harvest, while Shavuot signals ripened wheat ready for gathering. On the second day of Passover, Israel brought the first omer (biblical measurement) of the barley to the Temple as an offering, while Shavuot meant a first fruit offering from the wheat harvest. For this reason, the 49-day stretch between the two feasts is known as “Counting the Omer” and marks a progression from barley—a coarse grain used for feeding animals—to wheat—the ideal human nourishment.

This is where the connection between Ruth and Shavuot begins, explains Moshe Kempinski. Kempinski, an Orthodox Jew, has ample experience expounding Jewish truths to a Christian audience. His biblical gift store, Shorashim, offers the perfect souvenirs from Jerusalem—and a platform for Christians eager to explore Jewish perspectives.

Ruth arrived in Bethlehem during the barley harvest and started her process gleaning the coarse, lowly grain, Kempinski explains. “But in the end, she reaped untold blessings. Her great grandson, King David, was born and died on Shavuot.” Israel’s great shepherd king thus represented the perfected process his great grandmother began—from barley to wheat.

The birth of something new, something great and worthy, is often rough, coarse and lowly, continues Kempinski. Progressing from slavery to the point of receiving from the hand of God entails a commitment like that of the Moabite widow willing to glean barley to ultimately reap wheat.

Yet the connection between Ruth and Shavuot goes deeper still. The events surrounding the giving of the Torah unfolded quite dramatically. According to Exodus 19, the morning dawned with peals of thunder, lightning streaks through a blanket of thick, dark clouds, deafening booms of a trumpet, God’s presence covering Mount Sinai with smoke like that of a furnace and the mountain quaking greatly. Trembling at the fearsome sights and sounds, the Israelites panicked at the prospect of hearing from God firsthand and sent Moses up the shaking mountain to receive His instructions on their behalf.

When Moses returned, he “told the people all the words of the Lord and all the judgments” (Exod. 24:3). According to Kempinski, Israel responded with one of the most famous phrases in the Torah: na’aseh v’nishma—“We will do and we will hear/understand” (see v. 7).

“The order is important,” says Kempinski. Israel did not pledge to figure out God’s instructions before they acted on them. They did not undertake to understand the whats, whys and wherefores of God’s directives before they would walk them out. “When we stood at the foot of Mount Sinai, we promised to do what and as God commanded, and as a result of doing, we would understand.” On Shavuot, Israel accepted the yoke of the uncertain and unknown to embark on a journey with God.

“That’s what Ruth did too,” says Kempinski. “She told Naomi: ‘Where you go, I’ll go and your people will be my people,’” without knowing where they were heading and who they would meet when they got there. “She had the courage to embark on the journey of uncertainty and the unknown, regardless of where the journey led. That is the ability to walk in obedience first and then understanding. That is the secret of Shavuot. And that is the secret of Ruth.”

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.