×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Janet Aslin, BFP Staff Writer

“And you shall tell your son in that day [when the Lord brings you into the land which He promised to give you], saying ‘This is done because of what the Lord did for me when I came up from Egypt’” (Exod. 13:8 emphasis added).

The word haggadah (הגדה), which is the noun form of “to tell or expound” (להגיד leh-hah-geed) isn’t found in the Bible but its verb form certainly is. Strong’s H5046 nagad (נגד) appears 370 times in the KJV, primarily translated as “tell.” It is important to God that we “tell” others what He has done for us and who He is in our lives.

The Jewish people excel in their obedience to God’s command to “tell” and in many ways that may have been what held them together as a people throughout their long exile from the Land of Israel.

One of the biblical feasts especially concerned with “telling” is Pesach or Passover during which the haggadah plays an important role. All over the world, on the first night of Pesach, several generations of each Jewish family meet together in one home for the Seder (“order” in Hebrew) meal. They gather in obedience to the scriptural command to “tell your son” about how God brought His people out of the land of Egypt where they had been slaves. Not only are the participants remembering and retelling the Exodus story, they are also experiencing it for themselves.

Each guest will have a copy of the chosen version of the haggadah which contains everything necessary to conduct this meal—the oldest continuously observed religious ceremony in the world. Because the haggadot (plural) are meant to be used at the table, illustrating and explaining the Exodus, many bear the stains of wine and food—even those from the Middle Ages which are now valuable museum pieces—show evidence that they were once a well-loved part of family history. So what exactly does the haggadah contain?

Jewish tradition says that the haggadah was compiled between AD 200 and AD 500. Simply put, it contains the order of the Seder meal, blessings and prayers, the account of the Exodus, rabbinic commentaries or explanations and songs. These basic elements are contained in all versions of the haggadah, but there are many different variations as it has been adapted to meet the needs of Jewish people all around the globe.

Jonathan Safran Foer, novelist and editor of the New American Haggadah, writes, “In the absence of a stable homeland, Jews have made their home in books, and the Haggadah—whose core is the retelling of the Exodus from Egypt —has been translated more widely, and revised more often, than any other Jewish book.” Although there is a basic content for every haggadah, today there are over 2,000 different versions.

One of the earliest known stand-alone haggadot was from Spain, created in the 13th century. The number grew slowly: 25 printed versions in the 16th century, 37 in the 17th, 230 in the 18th increasing to 1,250 in the 19th century. These followed the style of one of four of the earliest editions to be printed: the “Prague Haggadah” of 1526–27, the “Mantua Haggadah” of 1560, the “Venice Haggadah” of 1609 or the “Amsterdam Haggadah” of 1695. But a major evolution began in the 20th century in an attempt to keep the Passover relevant to the younger generation and to inspire them to read with interest and reverence.

The earliest known illustrated Ashkenazi haggadah is the “Bird’s Head Haggadah” from southern Germany circa 1300. The artist’s use of bird’s heads rather than human ones may be related to a strict observance of the biblical prohibition against graven images.

The “Sarajevo Haggadah,” one of the oldest Sephardic haggadot, was created in Spain around 1350. It arrived in Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1894 where it was purchased by the National Museum. Although it had not been publicly displayed, it was well-known. When the Germans arrived during World War II, it was one of the first things they demanded from the museum. However, the museum’s chief librarian smuggled it out of the city and it was preserved. Since 2002, it has been on display at the National Museum in Sarajevo.

The “Venice Haggadah” of 1609 contains wood-cut illustrations done by an artist who was also a biblical scholar. He added details, such as showing the Israelites carrying the remains of Joseph as they crossed the Red Sea, which had not previously been included in other haggadot.

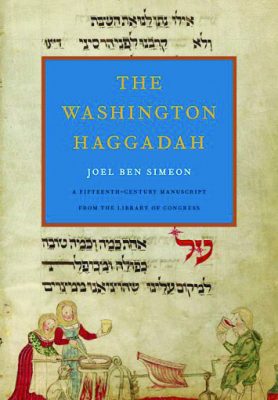

The “Washington Haggadah,” named for its location in the US Library of Congress, is an illuminated manuscript illustrated by Joel ben Simeon, the most prolific Hebrew artist-scribe of the 15th century. Not a sophisticated artist, yet his colored pen drawings earned him a place among the sixty top works named in Bezalel Narkiss’ book, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts.

The “Washington Haggadah,” named for its location in the US Library of Congress, is an illuminated manuscript illustrated by Joel ben Simeon, the most prolific Hebrew artist-scribe of the 15th century. Not a sophisticated artist, yet his colored pen drawings earned him a place among the sixty top works named in Bezalel Narkiss’ book, Hebrew Illuminated Manuscripts.

Modern haggadot abound. Today a printable haggadah can be downloaded from any number of internet sites; or read directly on a Smartphone or tablet. Yaakov Kirschen, creator of the Dry Bones cartoons, has published “the Dry Bones Passover Haggadah for the whole family—a completely traditional yet totally unique and exciting work.”

Jewish families have shared the tradition of Passover for many, many generations. When the youngest child present asks his father (or grandfather), “Why is this night different from any other night?” so begins the annual “telling” of an account that identifies them as God’s chosen people, the ones He led out of slavery in Egypt. Are we as faithful to tell about what He has done for us?

Photo Credit: www.wikipedia.org

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.