×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Janet Aslin, BFP Staff Writer

Photo by: Eddelene Marias/Bridgesforpeace.com

Recently a friend asked me to send her a mezuzah (Scripture box affixed to a doorway) from Israel. I had decided to buy it at Yad LaKashish, a wonderful organization in Jerusalem that gives elderly citizens the opportunity to work making Judaica and other items in a number of artistic workshops.

As I expected, I found the perfect mezuzah but was puzzled by the sign near the display case which read, “Scroll Not Included.” When I asked the salesclerk, I learned that, in order to be kosher, the scrolls must be hand-written by a scribe. Intrigued, I decided to do a little research.

Photo by: Tishchenko Inna/Shutterstock.com

There have been scribes ever since man began to use hieroglyphics or cuneiform symbols to communicate in a written form. In ancient Israel, scribes held important positions both as public administrators and as royal advisors. At one point, the term scribe was used to identify the person who mustered the troops (Jer. 52:25). By the time of King Hezekiah, the scribe had become one who interpreted Scriptures. One of the best-known scribes was Ezra, whose public reading of the Law (Neh. 8–10) signaled the nation’s return to God and the observance of His Law. The profession of the scribe continued to gain influence after the destruction of the Second Temple. Tyndale’s New Bible Dictionary says that “after AD 70 the importance of the scribes was enhanced. They preserved in written form the oral law and faithfully handed down the Hebrew Scriptures.”

With the advent of the printing press, the need for scribes vanished from most of the world. One exception, however, exists within the world of Judaism. Because of their reverence and respect for the Word of God, Jewish scribes can be still be found, meticulously writing by hand the sacred texts of the Torah (Gen.–Deut.).

The word for scribe in modern Hebrew is sofer (סופר) which literally means “one who counts.” This makes sense when you consider the fact that the scribe is counting each letter and word of the Torah as he writes, following precise rules set forth in the halacha (collective body of Jewish religious laws derived from the Torah).

More specifically, today’s Jewish scribe is known as a sofer stam ((סופר סת”ם with stam being the acronym for the three articles that must be written by a scribe: Sefer Torah (S), tefillin (T) and a mezuzah (M).

Although there is some debate within Jewish circles as to whether or not women can become scribes, generally speaking the role falls to men who observe the Jewish law, keep Shabbat, keep kosher, and pray every day. On his blog, Rabbi Berel Wein provides the following description: “The task of a scribe is certainly a most exacting one. It requires infinite patience, good writing and artistic skills and immense powers of concentration. It is not a task for the faint of heart and weak of hand.”

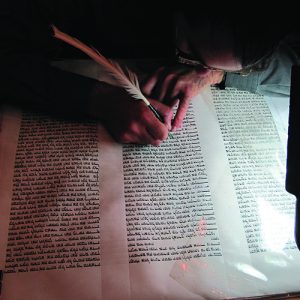

The accepted method of learning to become a scribe is the age-old one of apprenticeship to an experienced scribe. The student must learn by memory and practice more than 4,000 halachic rules governing the act of copying the sacred texts of the Torah. For instance, for each letter there is an average of 20 rules governing its formation. Attention is paid to the “white space” around and within each letter. Parchment must come from the skin of a kosher animal, the quill from a kosher fowl (goose or turkey) and there are instructions for the preparation of the black ink.

The sofer stam is not just a copyist. He must write with reverence and awe, with the right intentions. It is not a job, it is a vocation. With all the care taken for the writing of the Torah, even more is taken when the scribe writes the name of God. According to the Judaism 101 website, “In Jewish thought, a name is not merely an arbitrary designation, a random combination of sounds. The name conveys the nature and essence of the thing named.” Therefore, special care is taken that the written name of God is not erased or defaced. If the scribe makes an error when writing God’s name, the parchment cannot be destroyed but must be buried or stored in a safe place (called a genizah which means reserved or hidden).

Mezuzah – Photo by: Mikhail/Shutterstock.com

Back to the mezuzah—what exactly does it include? Inside a mezuzah there are two Scripture passages. According to halachic law, the text is exactly 713 letters on 22 lines, written by a trained scribe on specially prepared parchment. It may be written in the calligraphy of the Ashkenazi (European) or Sephardi (Middle Eastern) Jews but the content is identical.

The first passage, Deuteronomy 6:4–9 begins with the familiar words of the Shema: “Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one!” and ends with the command that Jewish people have kept for more than 3,000 years: “You shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates” (v. 9). The second passage, Deuteronomy 11:13–21, describes the blessings (or curses) that will come as a result of obedience (or disobedience) to God and concludes by exhorting the Israelites to teach God’s words to their children and to “write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates” (v. 21).

When we look at the beautifully designed mezuzah cases—and there are many different types and styles—let’s not lose sight of the treasure that lies within and the scribe’s heart of reverence when he inscribed it.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.