×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Ilse Posselt, Correspondent, BFP News Room

6 October 1973 dawned without a hint of the perils to come. It was the Day of Atonement—or Yom Kippur in Hebrew—the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. And the people of Israel observed it the way their fathers and their fathers’ fathers did for countless generations—prostrated in fasting and prayer.

Since sundown the night before, every store, restaurant and market in the Jewish nation had been shut tight. Schools and offices closed their doors early the previous afternoon. Highways, streets and village lanes where traffic usually bustled lay deserted. Even the skies were empty, with Israeli airspace a no-fly-zone on Yom Kippur. Radio and television stations had spoken their final word and disappeared from the airwaves until after the fast. A holy silence hung over the land of promise—broken only by the snatches of prayer drifting from synagogues and homes.

Just after 2 p.m., the wailing scream of air raid sirens brought a swift end to the age-old Yom Kippur observances. An Arab coalition, led by Egypt and Syria, had launched a coordinated surprise assault against the Jewish state on multiple fronts. Israel was—once again—forced into a war she wanted no part of, and her sons and daughters left their places of worship to run to her defense.

This year marks the 42nd anniversary of what history would later call the Yom Kippur War. Almost half a century has passed. Ancient history, some would say. But those who lived through the terrible days of uncertainty and fear remember them with a clarity that no amount of time or distance can erase.

The Yom Kippur of 1973 was particularly special for Yaakov. He had celebrated his 13th birthday—and his Bar Mitzvah (coming-of-age ceremony for Jewish boys aged 13)—the month before. “It was my first Yom Kippur as a man,” he recalls, “and my abba (father) and I were on our way to the synagogue.”

Jerusalem was quiet, he remembers, the type of quiet that only wraps itself around the city once a year for the Day of Atonement. Suddenly the air shook with the sound of fighter planes screeching south. “The look on my abba’s face told me something was very wrong. Deep down I think I knew. Because planes do not fly over Israel on Yom Kippur—unless they are forced to.”

Yaakov and his father never made it to the synagogue that day. A few minutes later, the air raid siren screamed in the Jewish capital and the people of Israel had to make a snap transition from prayer and fasting to the reality of war.

“It is funny the things you remember the best,” says Yaakov. “After we got home, Abba walked straight to the refrigerator, opened the door and grabbed the first thing he could find. It was watermelon—slices left over from the day before. He picked a piece for himself and one for me. Then he spoke for the first time, ‘The fast is over. Something terrible happened.’ That was when I knew we were in big trouble.”

Yaakov’s abba was right. The Arab coalition’s surprise attack had dealt the Jewish state a devastating blow. On the banks of the Suez Canal, less than 500 Israeli troops armed with a paltry 3 tanks faced the onslaught of some 600,000 Egyptians, 2,000 tanks and 550 aircraft. The situation on the northern border was similarly dire. The might of the Syrian army stood poised for an invasion, armed with almost 1,500 tanks. The only thing blocking their way was a fragile buffer of 180 Israeli tanks.

Yaakov’s abba was right. The Arab coalition’s surprise attack had dealt the Jewish state a devastating blow. On the banks of the Suez Canal, less than 500 Israeli troops armed with a paltry 3 tanks faced the onslaught of some 600,000 Egyptians, 2,000 tanks and 550 aircraft. The situation on the northern border was similarly dire. The might of the Syrian army stood poised for an invasion, armed with almost 1,500 tanks. The only thing blocking their way was a fragile buffer of 180 Israeli tanks.

The Jewish state’s enemies chose the specific date of attack with meticulous care. Since many Israeli soldiers had been granted leave for Yom Kippur, the Egyptian and Syrian forces would face far less resistance on Israel’s borders. Moreover, with all of the Jewish state engaged in fasting and prayer, the Arab coalition hoped for a quick victory.

Israel’s enemies meant to use Yom Kippur as a weapon against the Jewish state. However, in the end, the Day of Atonement served as a tremendous advantage.

“It is a miracle that they attacked on Yom Kippur,” says Eli. “This is the only day on which you will find all the people together in one place—everybody is in the synagogue or at home.”

Eli speaks from experience. He was 16 when the war broke out, living in a tiny village close to the Mediterranean Sea. “Our house was the last one, almost outside the village. It was about 2 p.m. and I was standing outside in the front yard. All of a sudden a car came roaring up to the gate, a man jumped out and asked for directions.”

Eli was shocked. “Nobody drives on Yom Kippur,” he explains. Yet he soon learned the reason behind the man’s unorthodox behavior. Since there were no radio broadcasts or telephone services on the Day of Atonement, Israel had to find another way of mobilizing her men and calling up reserves.

“The army sent buses to specific pick-up points,” recalls Eli. “They then sent people in cars to spread the word in the villages that war had broken out. These people knew exactly where to go—straight to the synagogues of course. And the men of Israel came out—still wrapped in their prayer shawls—to defend their country.”

Israel started out the Yom Kippur War at a terrible disadvantage. Caught by surprise and vastly outnumbered, the odds of victory were so slim that the cabinet made preparations for a government in exile. For the umpteenth time, complete annihilation seemed a distinct possibility.

Less than a week later, the tide had turned. Having won decisive victories on the northern and southern borders, the Israeli forces had an open road to the Syrian capital. Moreover, with the Egyptian army surrounded in the Sinai desert, Israel had Cairo well within her sights.

“Against all odds” is a phrase that seems to describe the majority of the Jewish state’s military triumphs. The Yom Kippur War was no different. Israel emerged victorious. Yet the cost was terrible—unbearably so.

“More than 2,500 of our boys died,” says Yaakov, suddenly looking old. “We did not want this war. We did not want the war before that or the one before that. And we did not want any of the ones that came after. But this is our home. This is Israel. And we will defend her always.”

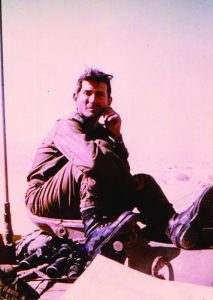

Photo Credit: Lt-Col. Avi fur/IDF Blog

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.