by: Rev. Cheryl L. Hauer, International Development Director

www.freeimages.com

The ability to communicate through spoken and written language is a remarkable gift God has given to mankind. However, that very language can sometimes diminish our understanding rather than enhance it. Take, for instance, the word love. For students of the Bible, there is no word that is more important. Although there are others that appear more frequently in the pages of Scripture, there is no concept that is more prevalent.

The Bible is, in fact, an epic love story from cover to cover, and in it, we are repeatedly enjoined to love—one another, our neighbor, the stranger among us, even God Himself. Both the Tanakh (Gen.–Mal.) and the Writings of the Apostles tell us that the greatest of all God’s commandments requires that we love. And yet, in our modern world, there are few words, if any, as over-used and misunderstood as the word love.

www.freeimages.com

Unlike Hebrew which has a number of words to communicate the nuances of love, English really has only one. Somehow, I must adequately express my feelings for my father, my husband, my dog, my car, my cup of coffee, the book I am reading and that amazing bite of chocolate I just had with only one word at my disposal. Cyberspace, book stores and movies are teeming with it. Every teenage girl dreams of it, we fall in and out of it, and everything from my favorite color to the passion I have for my husband is summed up by it. Love, love, love. It means everything. And consequently, it has come to mean very little.

www.freeimages.com

But to the writers of the Bible, love was a matter of the utmost priority. When the Lord passed before Moses and defined His character for all generations, He was speaking, He said, to those who love Him. In that discourse, He declared love as a part of His very nature. He also repeatedly spoke to the Israelites of His love for them as the impetus for the multitude of blessings He would pour out on them, a love that was everlasting and unconditional. In the Writings of the Apostles, Paul speaks often of love, making it clear that there is nothing higher on God’s priority list; it is even more important than faith or hope. Without love, he said, we are just a bunch of clanging cymbals, making a lot of meaningless noise. And both testaments emphasize the supreme and foundational importance of loving God.

To the ancient followers of the Lord, love could not be divorced from action. The Hebrew word ahava (אהבה) is defined as having a deep intimacy of action and emotion accompanied by a strong desire to be in the presence of the one loved. In verb form, it means to provide for and protect, to give. In that paradigm, it was impossible to fall in and out of love; love was a choice to behave in a certain way.

“I will love you, O LORD my Strength,” the psalmist says. He is stating his commitment to a life of self-sacrifice, his willingness to subordinate his desires to those of his God and embrace the divine definition of what is right and good. Certainly that ancient understanding of love was not devoid of romance and passion, the Bible makes that very clear as well. But the focus was on giving, not receiving; on commitment and choice, not feeling; on emulating the God of the Universe whose love is unfailing and all-encompassing.

Today, our understanding of love has become clouded by a desire for emotional experience and self-satisfaction. In my search of 15 different dictionaries, not a single definition included choice, commitment or action. But all had certain things in common: an intense feeling of deep affection; a strong attraction that includes sexual desire; a feeling of deep attachment; an intense emotion of warmth; wholehearted pleasure in; a feeling of kindness, enthusiasm or concern.

So that’s what it’s really all about? “I love how you love me,” says the old song. It’s how you make me feel that is important. Even much of our Christian music today focuses less on God and our service to Him than on us and how He makes us feel. How do we reconcile those definitions with a command to love the Lord with our whole hearts? Do we enter His presence and wait for that “emotion of warmth” to overtake us? If there is no feeling, then what? And what about those times when there is no pleasure, only difficulty, disappointment or strife? What does it mean, Lord, to love you?

Rabbi Shraga Simmons of aish.com tells the following story:

In 1945, Rabbi Eliezer Silver was sent to Europe to help reclaim Jewish children who had been hidden during the Holocaust with non-Jewish families. How was he able to discover the Jewish children? He would go to gatherings of children and loudly proclaim the Shema: “Hear, O Israel, The LORD our God the LORD is One” (Deut. 6:4).

velveteenrabbi.blogs.com

Then he would look at the faces of the children for those with tears in their eyes—those children whose distant memory of being Jewish was their mothers putting them to bed each night and saying the Shema with them.

The Shema, a collection of verses from Deuteronomy 6, 11 and Numbers 15, is the foundational creedal statement of the Jewish people. It is a declaration of faith, a pledge of allegiance to One God and an affirmation of the commitment to love Him. It is said upon rising in the morning and before going to sleep at night, when praising God and when beseeching Him. It is the first prayer that a Jewish child is taught and the last words a Jewish person says prior to death.

Throughout the ages, the cry of the Shema has symbolized the unbreakable covenantal bond between the God of Israel and His people even in the darkest of situations. And when Yeshua was asked what was the greatest of all the commandments in the Torah (Gen.–Deut.), the Shema was His reply. “You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind, and with all your strength.” He continued, “…you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Mark 12:30–31).

ivn3da / shutterstock.com

The Hebrew word for heart is lev (לב). It comes from a root which means to be enclosed, in the interior or at the center. In Greek, the word is kardia (καρδία) which refers to the center of man’s inward life—the place that can be ruled by depravity or surrendered to divine influence. Modern psychology tells us that the mind is the purview of knowing, feeling and willing. But the ancients believed the heart was the center of man’s moral and spiritual life, and emotion and intellect flowed from it. As the emotional core, it was the well-spring of reverence, remorse, joy, sorrow, gladness and fear.

However, Scripture refers several times to the “thoughts and intents of the heart.” It was not only the intellectual and emotional center, but it was the volitional center as well. This was the seat of conscious resolve. Here, the hard choices were made, commitments established and then adhered to. It was the heart that made the decision and the whole being followed suit.

In the Cologne ghetto where hundreds of Jews hid from Nazi torment during World War II, an inscription was discovered not long after the end of the war. Scrawled across a stone wall by an anonymous author who was later evacuated to the ovens at Auschwitz, it read:

“I believe in the sun even when it’s not shining. I believe in love even when not feeling it. I believe in God even when He is silent.”

Like the psalmist’s “I will,” this was a choice, an incomprehensible decision to believe, love and trust when horrific circumstances called only for fear, resentment and hatred. This, like the Shema, was a declaration of faith and a pledge of allegiance. This was loving God with a whole heart.

The Hebrew word for soul is nephesh (נפש). Unlike our modern understanding of soul as the ephemeral reality of man that is somehow separate from the physical body, the ancients understood nephesh as the entirety of the human person. It literally means “living being,” and refers to the tangible aspects of life. Today, we are taught that man “has a soul.” The biblical definition, however, indicates that man is a soul.

In the Torah, nephesh refers to one’s entire being as a living person, including the heart, but everything else as well. When God breathed life into Adam, he became a nephesh. Clearly, everything about us should declare the majesty of the Lord. Our passions, hungers, perceptions, thoughts, appetites…all that is “us” was created to reflect the nature of the one true God. How we talk, how we spend our time, our actions and reactions…our entire beings are called to reflect the glory of God.

Rabbi Akiva was a second-century Jewish sage and leader whose teachings are still revered in Judaism today. Even though the Romans who occupied Israel at that time had forbidden the teaching of Torah, Rabbi Akiva continued to encourage his followers with the Word of God.

He was arrested and sentenced to a hideously painful death. With a large iron comb, his captors slowly scraped his flesh from his body, and as he was being tortured, he began to joyously recite the Shema. His students, who were nearly overcome with fear and grief, asked how he could praise God in the midst of such horror. He replied, “All my life, I have loved God with all my heart and all my strength. Now, I understand what it means to love Him with all my soul and I do so with joy.”

It is in Mark 12:30 that Yeshua refers to the Shema in His answer to a scribe who has asked, “What commandment is the foremost of all?” (Mark 12:28b). However, His answer varies somewhat from the Shema as it appears in Deuteronomy 6. Yeshua adds the injunction to love the Lord with all your mind. He uses the Greek word dianoia (διάνοια) which means deep thought and refers to the mind as a faculty of understanding, imagination and desire. When the scribe repeats Yeshua’s words back to Him, he actually uses a different word for mind, sunesis (σύνεσις) which means to bring together and refers to human intelligence.

It is in Mark 12:30 that Yeshua refers to the Shema in His answer to a scribe who has asked, “What commandment is the foremost of all?” (Mark 12:28b). However, His answer varies somewhat from the Shema as it appears in Deuteronomy 6. Yeshua adds the injunction to love the Lord with all your mind. He uses the Greek word dianoia (διάνοια) which means deep thought and refers to the mind as a faculty of understanding, imagination and desire. When the scribe repeats Yeshua’s words back to Him, he actually uses a different word for mind, sunesis (σύνεσις) which means to bring together and refers to human intelligence.

For most of the Israelites who were listening to this exchange, Yeshua’s inclusion of “mind” may have seemed a bit redundant. After all, these concepts had already been covered by the command to love the Lord with all your heart, man’s intellectual center; the functions of dianoia and sunesis, they believed, occurred in the heart.

However, since neither word seems to have a direct Hebrew equivalent, perhaps Yeshua was mindful of the fact that some of His listeners, maybe even this scribe, were Hellenized Jews who had been strongly influenced by Greek culture and thinking. In that paradigm, the mind and not the heart was recognized as man’s intellectual center. It was here, the Greeks believed, that reasoning happened, that knowledge and information were analyzed and brought to a conclusion. Perhaps Yeshua was making sure that all of His listeners, regardless of worldview, fully understood the implications of His answer.

We must surrender everything to God…nothing can be held back. Mocha.VP / shutterstock.com

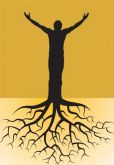

The Hebrew word translated strength or might in Deuteronomy 6 is me’od (מאוד). Its meaning is “very” and it brings a superlative emphasis to the word it is modifying. In Genesis 7:18, we read that the water “increased greatly (me’od) upon the earth.” In Psalm 47:9, the psalmist tells us that God is “greatly (me’od) exalted.” The word occurs over 300 times in this adverbial form in all periods of biblical Hebrew.

However, it only appears as a noun twice in the entire Bible. Once is in Deuteronomy 6:5 and again in 2 Kings 23:25 where King Josiah “turned to the LORD with all his heart, with his soul, and with all his might (me’od).” The Greek translation of the noun is “power” and the Aramaic “wealthy” while the vast majority of today’s English Bibles translate it “strength” or “might.”

However, many Jewish sages teach that in these two verses, me’od actually should be translated resources. Our commitment to loving God with everything that we are must transcend our physical selves to include everything that we have as well. Strength and power aren’t necessarily only physical attributes. They may also, along with wealth, refer to what a person has at his disposal. We must surrender everything to God, including our money and possessions, our loved ones and relationships, our community standing and professional positions, our tools and technology, our entertainment…even our time. Nothing can be held back.

Many Christians are surprised to discover that Yeshua’s instruction to love one’s neighbor as he loves himself did not originate in first-century Israel. As often happened, He was quoting the Torah. A central tenent of Judaism, this instruction appears first in Leviticus 19:18 which says, “You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the children of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.” Even though Yeshua was referring to this verse as part of the greatest of all commandments, it is interesting that He gave no further instruction or elaboration. He didn’t find it necessary to tell His listeners how to keep the commandment, just the importance of their obedience to it.

Many Christians are surprised to discover that Yeshua’s instruction to love one’s neighbor as he loves himself did not originate in first-century Israel. As often happened, He was quoting the Torah. A central tenent of Judaism, this instruction appears first in Leviticus 19:18 which says, “You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the children of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.” Even though Yeshua was referring to this verse as part of the greatest of all commandments, it is interesting that He gave no further instruction or elaboration. He didn’t find it necessary to tell His listeners how to keep the commandment, just the importance of their obedience to it.

Perhaps that is because those instructions are clearly found in the previous nine verses (Lev. 19:9–17). But first, let’s examine the use of the words “as yourself.” In the Hebrew, this term means according to or in comparison to. Are you as concerned about feeding your hungry neighbor as feeding yourself? Do you have as strong a desire to protect your neighbor as you do yourself? When you are warm and comfortable, or cold and miserable, do you consider the state that your neighbor is in? Is he as warm as you? As cold as you? And don’t forget that love’s emphasis in that ancient Hebrew world was on action. These weren’t just theoretical questions. They were real questions that demanded answers and action. Beginning in verse 9, the Torah is very clear what that action should be.

Bridges for Peace

Verses 9–10 instruct us to give generously from our own harvest to the poor and the alien; verse 11 demands that we refrain from stealing or dealing deceptively with our neighbor; verse 12 tells us not to swear in God’s name. We are told not to oppress, rob, or cheat our neighbor or exploit the poor with unfair wages; not to curse the handicapped or commit any injustice. We are instructed to consider each man fairly and refrain from slandering him or threatening him in any way. Finally, we are restricted from hating our neighbor, taking vengeance or holding a grudge. We are to love him.

In order to do that, we have to know him. We can’t help to meet his needs if we don’t know what they are. Finally, verse 18 ends with the powerful declaration, “I am the LORD.” Such a statement reminds us immediately that our neighbor is made in the image of God and is entitled to respect and justice. And it removes any thought that somehow, we can squeak by without loving our neighbor. It isn’t possible, He tells us. Loving your neighbor is how you love Him.

IgorSamoilik / shutterstock.com

As I meet with Christians around the world, I am encouraged that God is at work all over the globe preparing His Church for the days ahead. However, I am also concerned that many in the Christian world are facing crises because as a body, we have forgotten how to obey the greatest of all commandments. And there is only one answer for that very unfortunate reality. If we turn and cry out to Him, He is the God who is faithful and true, just and loving, kind and forgiving. He is the One who will draw us back to Him with cords of kindness if we but take a few baby steps in the right direction:

MikeMonahan / shutterstock.com

If I am obedient to the Lord out of duty, even if the duty is clear and required, I have obscured and perhaps missed a vital component of the action. My duty to the Lord must arise from my love for Him, not simply from my obligation to His word. Can I love God and not do what He asks? What kind of relationship would that be? Certainly not one where tenderness, intimacy and genuine concern motivate the action. Duty does not require love, but love certainly expects duty. To do God’s will is to love Him wholeheartedly—and act accordingly.

Buckner, Brett, “Staring into the void: God and the Holocaust,” The Anniston Star, 2005.

Brown Driver Briggs Online

Lieber, Rabbi Moshe. The Pirkei Avos Treasury, Ethics of the Fathers. Brooklyn NY:

Mesorah Publications Ltd., 2000.

Strong, James. Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance. Nashville TN: Crusade Publishers, 1990.

Vine, W.E. and Merrill Unger. Vines Expository Dictionary of Biblical Words. United

States of America: Thomas Nelson Inc., 1977.

www.aish.com

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.