by: Abigail Gilbert, BFP Staff Writer

Joshua established six cities of refuge, three on the east side of the Jordan and three on the west. Photo: vecteezy.com

The Torah (Gen.–Deut.) and Tanakh (Old Testament) are full of examples of the revolutionary laws and system of justice given to the Hebrew people. Compared to other laws and codes of the time—Hammurabi’s Code, the Middle Assyrian and Babylonian lists to name a few—the Torah offered a system of justice that prioritized human life more than any other law of its time; it was a nuanced covenant that sought to weave justice into worship, so that the penalties varied to fit individual circumstances.

Of course, the judicial system required harsh punishment for cases of violent crime and murder. In the Torah, spilled blood can only be atoned for with the blood of the one who committed the crime, preferably at the hands of the “avenger of blood”—the closest male relative. It was his right and duty to slay the murderer, to “put away the guilt of innocent blood from Israel” (Deut 19:13).

Yet even in this strictest retribution, God provided an “out” to protect His people from the blood feuds that plagued so many of the surrounding nations. In cases where a person was killed by accident, God told the people of Israel to set aside “cities of refuge” where the person responsible for the death could be safe from the avenger of blood.

These cities tell us much about the history of Israel, its system of justice and its God. He provided an answer not only to protect the one who accidentally spilled blood, but to save the man seeking revenge as well.

We first read about the biblical cities of refuge near the end of Numbers, when God tells Moses to set aside six cities of refuge in addition to the 42 other cities given to the tribe of Levi (Num. 35:6). The six cities were to be places of safety for any “manslayer” who accidentally killed someone. Later in the Torah there is an example of the kind of accident that would qualify: “…as when a man goes to the woods with his neighbor to cut timber, and his hand swings a stroke with the ax to cut down the tree, and the head slips from the handle and strikes his neighbor so that he dies…” (Deut. 19:5).

This isn’t a premeditated, malicious or even radically careless act. Still, any tragedy where blood was spilled demanded recompense (Gen 9:6; Lev 24:17); so the cities of refuge provided an “out” from the harsh application of the law of retribution. If the manslayer could escape to one of the six cities, he was safe from the wrath of the avenger of blood.

The rules for the cities are outlined in both Numbers and Deuteronomy, and in Joshua chapter 20 the LORD reiterated His exhortation to Joshua as the Hebrew people were finally entering the Promised Land. Joshua established six cities of refuge, three on the east side of the Jordan and three on the west. The cities were evenly spaced from north to south. Kedesh, the northernmost, was in the Galilee, while the southernmost, Hebron, was built about 20 miles (32 km) south of Jerusalem (Joshua 20:7–8).

Six tribes were represented in the six locations: Kedesh was surrounded by land belonging to Naphtali, Shechem belonged to Ephraim, and Hebron was in the mountains of Judah. On the east side of the Jordan, Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh were represented. The cities of refuge and the land upon which they were built belonged entirely to the tribe of Levi.

As merciful as the name sounds, cities of refuge were, in fact, places of judgment. The manslayer could only stay if he or she was declared innocent of premeditated murder and malicious intent. If a man fled to the city, his case was heard at the gate by elders from within the city. If they found him guilty, he wasn’t allowed inside, and was instead turned over to the avenger of blood to be killed. The city of refuge was simply there to protect the right of due process and make sure no offending man was “cut down” before his case was heard by the congregation.

In some ways, the cities of refuge were prisons without any allowance for ransom or “blood money.” The manslayer could conceivably live out the remainder of his days within the walls of the city. There was one caveat to this rule. The “statute of limitations” on the crime of accidental manslaughter ran out after the High Priest died—at that time the man could return to home and family without fear of retribution.

Life within the city had its benefits, other than the obvious safety and escape from death. The cities were cared for by the Levites, who provided a healthy learning environment for the person found guilty of accidental manslaughter. If the offender ever returned to the world outside the walls of the city, he would be a better citizen and follower of God. Being exposed to a lifestyle that, as Adam Clarke wrote in Clarke’s Commentary, “by careful use of which [the offender] might grow wiser and better; secure the favor of his God, and a lot of blessedness in a better world.”

Cities of refuge were an obvious extension of mercy to accidental manslayers, saving them from sudden death, but they were also a less obvious mercy to the avenger of blood.

In Deuteronomy we read that the system is set up “lest the avenger of blood, while his anger is hot, pursue the manslayer and overtake him” (Deut 19:6). There’s a clear understanding that the kinsman, acting out of passion and grief, could try to enact personal justice before the case had a chance to be heard by the congregation for the meting out of proper justice.

But there wasn’t just an allowance for the avenger of blood in Scripture. There’s a duty. Charles Lee Feinberg writes in his article, “The Cities of Refuge,” that the Hebrew idea of “man in God’s image” lent force to the process of blood revenge described in Genesis: “Whoever sheds man’s blood, by man his blood shall be shed; for in the image of God He made man” (Gen 9:6). Feinberg writes that since God is Creator, and therefore Lord over human life, “a blow at this life is a blow at God Himself. Blood revenge becomes a religious duty, not merely a matter of honor.”

There is the possibility, then, that even if the closest kinsman was not out of his mind with rage and anger over the accidental death of his family member, he would still have a duty to kill the perpetrator. Here again, the cities of refuge provided a merciful alternative, giving the next of kin a legal, honorable and godly way to let the feud die without further bloodshed.

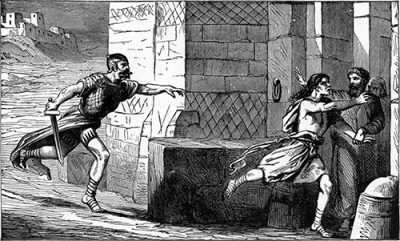

The process of justice set up around the cities of refuge was not simply a race between the avenger of blood and the one accused—it involved the community as well. We read first in Numbers that the congregation shall “judge between the manslayer and the avenger of blood” (Num. 35:24), then later in that same chapter, “and the congregation shall return him to the city of refuge where he had fled” (v. 25).

The congregation had a few main roles. They had a responsibility to intervene in the hot-headed moments following a tragic accident, where the avenger of blood may not have seen the situation clearly. They were also called to exercise wisdom in judging the truth of the deadly accident. They, like the cities of refuge, stood in the way of injustice and protected the accused’s right to a fair hearing.

So who made up this “congregation?” In Joshua 20:4 we read that the manslayer declared his case before the elders of the city of refuge in which he meant to shelter. In Numbers 35:24–25 and Deuteronomy 12:19, we read that the manslayer’s immediate community was also supposed to get involved, with the elders “of his city” delivering him from the hand of the avenger of blood.

The congregation stood in the way of injustice and protected the accused’s right to a fair hearing. Photo: Charles Foster/wikimedia.org

The local community also had a geographical investment. Not only had six tribes given up land to the Levites for the cities to sit upon, but they were commanded to keep the cities easily accessible, “You shall prepare the roads” (Deut 19:3), something many commentators interpret as keeping the roads in good repair and well-marked, so that nothing could hinder the accused from getting to the seat of justice quickly.

We’ve already discussed the requirements for safe harbor in a city of refuge. The accidental death had to be out of the perpetrator’s control, completely accidental, and not the result of any extreme negligence. If, for example, a man had an ox that had gored someone in the past, and did nothing to keep it from killing someone in the future, the subsequent crime was considered extremely negligent and punishable by death (Exod. 21:28–29).

But there’s another major qualifier for innocence, assuming no negligence is found. “And this is the case of the manslayer who flees there, that he may live: Whoever kills his neighbor unintentionally, not having hated him in the past—” (Deut. 19:4). This sentiment is carried over from Numbers, where the innocent man worthy of shelter in a city of refuge is described as having committed the crime “while he was not his [the victim’s] enemy or seeking his harm” (Num. 35:23).

This concept of judging by the inclination or intent of the heart is not limited to the Torah. In the Writings of the Apostles (New Testament) Jesus/Yeshua takes the command not to murder a step further, saying “But I say to you that whoever is angry with his brother without a cause shall be in danger of the judgment. And whoever says to his brother, ‘Raca!’ shall be in danger of the council. But whoever says, ‘You fool!’ shall be in danger of hell fire” (Matt. 5:22). The word raca came from an Aramaic word meaning “empty-headed” and was a common term of derision, much like the “You fool!” found later in the verse. Here, Jesus places emphasis on the heart, telling His disciples that an angry, murderous spirit, even without physical action, can cause harm and therefore has consequences.

1 John 3:15 drives this point home, saying “Whoever hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him.” Just as the manslayer was judged by the purity of his heart and intentions, so are we judged before the Lord, for “I, the Lord search the heart, I test the mind, even to give every man according to his ways, according to the fruit of his doings” (Jer. 17:10).

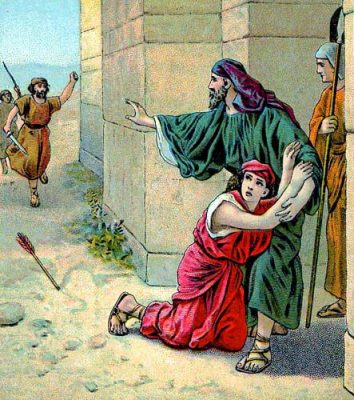

Without an understanding of the biblical background, the modern term refers to a city that accepts those outside the law without judgement. Photo: Providence Lithograph Company/wikimedia.org

The Lord is not fooled by outward appearances. The same God who judges the innocent heart of an accidental manslayer sees the heart of each and every one of us. This should encourage us to examine our motivations as well as our actions, and rein in reactions that are coming out of a heart of hate, anger or derision.

Today, we don’t have physical cities of refuge to run to, nor do we need them with our current earthly judicial system. An avenger of blood in today’s society does not have the right to carry out his own vigilante justice and would be considered a murderer if he did so.

Even in ancient times, cities of refuge were an anomaly handcrafted by God for His chosen people and were not found in neighboring nations. In recent years, there has been some attempt at reviving the idea of the city of refuge, or the “sanctuary city,” especially in the United States, but without an understanding of the biblical background, the modern term refers to a city that accepts those outside the law without judgment. As we’ve discussed, this understanding is somewhat different from that behind the cities of refuge, which judged the guilty and only harbored accidental offenders.

Still, the modern church can learn from ancient cities of refuge. We have a role in facilitating justice, metaphorically “making the way smooth” to a place of peace again. In the Writings of the Apostles (N.T.) Paul quotes Deuteronomy 32:35, saying “Beloved, do not avenge yourselves, but rather give place to wrath; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is Mine, I will repay’ says the Lord” (Rom. 12:19). Paul writes that we shouldn’t repay evil for evil, exhorting believers to live in peace with all men. The congregation’s role in the cities of refuge helps bridge the gap between “eye for an eye” justice and God’s desire for man to live in peace, leaving revenge to Him.

It’s the role of the community to step in, making the way to peace and communal relationships smooth, just as they were to keep the roads clear to cities of refuge.

Additionally, the “eye for an eye” justice system was not about vengeance but about the limitation of retaliation. Jarrod McKenna writes in his article “Which is it? Eye for an Eye or Turn the other Cheek?” that in Jesus, violence is not just limited, it’s transformed. “There is nothing passive about Jesus turning the other cheek in the face of injustice (John 18:23),” he writes. “To turn the other cheek is to practice the provocative peace that embodies the healing justice of the Kingdom.”

I love the way he says that: the pursuit of peace isn’t passive, it’s provocative. It’s part of the battle for justice in God’s kingdom. In the time of Moses and Joshua, that battle looked like a well-marked trail to a place of refuge so the avenger of blood and the manslayer were both spared from a continuing blood feud. It was, in some cases, an eye for an eye. Today, we still need to be a connected part of our community, so that when disagreements arise we work together to get the offended and the offender to arrive at a solution.

Clarke, Adam. “Joshua.” Clark’s Commentary: Genesis-Esther. 80-81.

Feinberg, Charles Lee. “The Cities of Refuge.” Bibliotheca Sacra. 103, 1946: 411-17.

Tenney, Merrill. “Cities of Refuge.” The Zondervan Pictoral Encyclopdia of the Bible. Grand Rapids: The Zondervan Corporation, 1976. 869-871. Print.

Jarrod McKenna, “Which is it? Eye for an Eye or Turn the Other Cheek?” Patheos (blog), April 1, 2011, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/christianpiatt/2011/04/which-is-it-eye-for-an-eye-or-turn-the-other-cheek-banned-questions/

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.