×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Rev. Cheryl L. Hauer, International Development Director

liza1979/shutterstock.com

Everyone loves a good party, and for the Jewish people, the holiday of Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles) starts the year off with just that. It’s a time to sleep under the stars, eat outside instead of in and invite people you know, and even people you don’t, to join you for joyous times of food and fun. Of course, it has its serious side as well, but Sukkot is a welcome, enjoyable conclusion to the 60 days of introspection, fasting and repentance that are Judaism’s High Holidays.

As summer gives way to fall and the evenings are touched with a welcome drop in temperature, families throughout Israel open their storage areas and remove their supplies for building a sukkah (booth). Synagogues, restaurants, even office buildings erect their own versions of these temporary shelters as well, as do Jewish people the world over. Decorations run the gamut from paper chains and plastic fruit to strings of sparkling lights and framed pictures of famous rabbis. Families eat as many meals as possible in their sukkahs during the holiday, and often invite guests to join the festivities. Sleeping in the sukkah is common, too, and many a Jewish child falls asleep gazing up at the stars, tucked safely into a sleeping bag while the story of the Israelites’ 40-year trek through the desert is told and retold.

There is much, much more to Sukkot, however, than the festive atmosphere of the sukkah. In order to appreciate the profound spiritual depth of this very special celebration, we need to look back for just a moment at the 40 days that have led up to the holiday.

In our last two teaching letters, Rebecca Brimmer took us on an amazing and life-changing journey through Judaism’s most sacred season. In the month of Elul, we took stock of our lives, repented of our sins and drew near to God in joyful submission. Next came the month of Tishrei with Rosh HaShanah, the Jewish New Year, followed by the ten Days of Awe, another period of prayer and repentance. Finally, we arrived at Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), the holiest day on the Jewish calendar, when Jewish people everywhere fast from food and water for 25 hours. Judaism teaches that these very somber days determine the destiny of the lives of those whose hearts are stirred by the call of the shofar (ram’s horn), whose tears are shed over sins committed and whose heartfelt prayers reach the very throne room of God.

But it doesn’t end there. There are four days between Yom Kippur and Sukkot, an important time of transition, as we move from the Days of Awe to the Days of Joy. During the first half of the month of Tishrei, mankind was reminded that God is King over all creation. Rosh HaShanah celebrated His coronation, acknowledged His sovereignty and prompted His people to submit anew to His will. We encountered God as Judge, the One who holds absolute authority over our lives.

shutterstock.com

And now the sages say, it is time to celebrate. In his book 60 Days, author Simon Jacobson uses an example from nature. How awesome it is, he says, to watch a thunderstorm raging over the sea. The massive waves and raw power may cause us to feel inspired, even uplifted by the beauty of such a sight. But even as we are profoundly moved, we are only relating from a distance. To plunge in and immerse ourselves in the water requires that we let go of fear and draw near. So it is, Jacobson says, with the Jewish people and their relationship with God. They have stood before the King, like Queen Esther of old, and He has extended His scepter. Now it is time to take the plunge, to draw near and immerse themselves in that incomprehensible ocean of love. And there can be no reaction but inexplicable joy. What should happen after Yom Kippur? Dancing in the streets!

In the Torah, the Lord clearly instructed the Israelites regarding His moed, those sacred times that He had set apart to meet with His people. Of those biblical feast days, three were considered pilgrim festivals, holy days on which the men of Israel were to make pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem. Each of them has a designation by which it is known in the texts of Jewish liturgy and tradition. Pesach (Passover), commemorating the Exodus from Egypt, is known as “the time of our freedom.” This is the holiday of national emancipation. Shavuot (Feast of Weeks), the anniversary of the Sinai revelation, is “the time of the giving of our Torah.” Sukkot is called “the time of our joy.”

That shouldn’t surprise us, because God makes it very clear that joy is to be the hallmark of this celebration:

“And you shall take for yourselves on the first day the fruit of beautiful trees, branches of palm trees, the boughs of leafy trees and willows of the brook; and you shall rejoice before the LORD your God for seven days” (Lev. 23:40).

In Deuteronomy 16, He reiterates those instructions, directing the Israelites to rejoice because He cares for them. He is their provision, He reminds them, and that is as true today as it was for those who, millennia ago, wandered in the desert for 40 years. At no other time in history was that joy so apparent, however, as during the celebration of Sukkot in the Temple. In first-century Israel, Sukkot was so important it was often referred to as “The Feast,” and the events of the final day so critical, it became known as “the Great Day.”

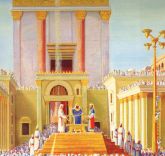

Imagine for a moment the ancient city of Jerusalem, tucked among the mountaintops, the glorious Temple to the God of the Universe sparkling in the sun. The hillsides surrounding the city, usually covered only by trees and agricultural areas, are now alive with pilgrims. Jewish people from throughout the Land of Israel, and other parts of the world as well, have come to celebrate the Feast of Tabernacles in the Temple. As night falls, thousands of campfires dot the hillsides as families erect their temporary shelters and prepare for the incredible events of the coming days. A spirit of joyful anticipation fills the air as fathers tell their children of the amazing things they are about to see and the incredible encounter with God that awaits them.

Trumpet blasts echo through the hillsides, calling worshipers to the Temple

Finally, the first night of the festival arrives and trumpet blasts echo through the hillsides, calling the worshipers to the Temple. The outer courts have been prepared with wooden bleachers for the observers and the altar decorated with willow branches, their soft leaves whispering in the evening breeze. The festivities begin with the lighting of the festival lamps. Giant golden poles, nearly 75 feet (23 m) tall, have been erected, each holding four large containers. Young priests-in-training climb ladders reaching to the top of the huge lamp stands, carrying large jugs of oil.

When at last the containers are filled, the trumpets blast again and the music begins. Priests with a variety of musical instruments line the steps, providing background for the Levitical choir as psalms of praise are sung. At just the appropriate moment, the young priests light the wicks in the lamps and light floods the Temple. So much light, the sages say, that not a courtyard in all of Jerusalem remained dark, every inch of the city being illuminated by the Temple lamps.

Throughout the entire night, the Temple court is alive with music, singing and dancing led by the elders of Israel, the sages, the greatest scholars and the most pious of the community. Disregarding their station in life, these leaders of Israel dance with abandon in honor of the God of Israel, some even juggling torches as they dance. The young are carried on the shoulders of the old as the celebration continues until dawn approaches.

Suddenly, the sound of the shofar pierces the night air and the worshipers are called to cease their revelry and follow the priest through the Eastern Gate to the pool of Siloam. Here, a golden jug is filled with pure spring water and as the sun breaks the morning horizon, it is carried back into the Temple through the Water Gate. The procession is accompanied by joyful singing and trumpet blasts until the congregation gathers again around the altar.

As the High Priest climbs the steps, members of the priesthood circle the altar once, praising God and thanking Him for His loving-kindness while the water is poured out as a sacrifice. The water flows through small troughs strategically placed along the edges of the altar, bringing the sparkling liquid down the perimeter on each side and then together again to flow off the altar in a single stream into a special container below. Once the sacrifice is complete, dancing begins again until each exhausted worshiper makes his way back to his sukkah for some rest.

As the High Priest climbs the steps, members of the priesthood circle the altar once, praising God and thanking Him for His loving-kindness while the water is poured out as a sacrifice. The water flows through small troughs strategically placed along the edges of the altar, bringing the sparkling liquid down the perimeter on each side and then together again to flow off the altar in a single stream into a special container below. Once the sacrifice is complete, dancing begins again until each exhausted worshiper makes his way back to his sukkah for some rest.

Each night, as the scenario is repeated, the anticipation increases until finally the eve of the final day, that Great Day, arrives. Somehow, the Temple lights seem brighter, the singing more beautiful, the dancing more energetic than ever before. Fresh willow branches adorn the altar and the smell of incense fills the air. Again, at dawn, the sound of the shofar draws the worshipers to join the High Priest on his trek to the pool for water. Singing and praising accompany the procession back through the Water Gate and to the altar. Once more, the High Priest climbs the steps, but this time members of the priesthood circle the altar not once, but seven times, reciting psalms and praising God.

This time, water is only poured out on one corner of the altar, as simultaneously, wine is poured out on the other. The two liquids each make their way down the perimeter of the altar and suddenly, a hush falls upon the congregation. Singing stops, music is silenced, as everyone waits with expectation. In order for the sacrifice to be acceptable, the water and wine must both reach the point of convergence at exactly the same time, mingling together as they tumble off the altar and into the container below. It is as though all Israel holds its breath as they wait to see if this sacrifice, the water libation, will accomplish its purpose. When it does, a mighty shout of joy is heard throughout the Temple courts and dancing begins again.

This time, water is only poured out on one corner of the altar, as simultaneously, wine is poured out on the other. The two liquids each make their way down the perimeter of the altar and suddenly, a hush falls upon the congregation. Singing stops, music is silenced, as everyone waits with expectation. In order for the sacrifice to be acceptable, the water and wine must both reach the point of convergence at exactly the same time, mingling together as they tumble off the altar and into the container below. It is as though all Israel holds its breath as they wait to see if this sacrifice, the water libation, will accomplish its purpose. When it does, a mighty shout of joy is heard throughout the Temple courts and dancing begins again.

The Talmud proclaims that he who has not seen the water libation ceremony in Jerusalem’s Temple has never seen real joy. It is this heritage of unmitigated elation in worship of the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob that informs the modern Sukkot celebration. Even though there is no longer a Temple in Jerusalem or a water libation ceremony, the knowledge that God is a fount of love, the protector of Israel, and the Beloved of the Jewish people causes that same joy to spring up in the hearts of His people today.

For Christians, the water libation ceremony has special significance as well. The Gospel of John tells us that Yeshua made His way to Jerusalem for the feast of Sukkot. On the last day, we are told in John 7:37, that Great Day of the feast, He stood with countless other worshipers in the Temple courts. As that expectant hush fell over the congregation during the water libation sacrifice, His lone voice was heard, “If anyone thirsts, let him come to me and drink. He who believes in me, as the Scripture has said, out of his heart will flow rivers of living water” (John 7:37–38). Many Christian scholars also believe that it was in the courtyard where the giant golden lamp stands stood to illuminate the city of Jerusalem that Yeshua proclaimed, “I am the light of the world.”

Today’s Sukkot celebrations vary somewhat from country to country. In Israel, for example, the celebration is eight days long: seven days of Sukkot and the eighth day marking both Shemini Atzeret (Eighth Day of Assembly) and Simchat Torah (Rejoicing in the Torah). In the Diaspora, however, Shemini Atzeret is celebrated on the eighth day and a ninth is added for Simchat Torah. But the messages of Sukkot are the same no matter where you are. Building the sukkah and embracing the joy of the festival have many lessons to teach.

While some people begin building the sukkah the minute Yom Kippur is over, and others wait until Erev Sukkot, the significance of fulfilling God’s instruction to do so goes far beyond friendly gatherings and sleep-overs. One such Sukkot lesson is that God’s people are but sojourners here, just passing through this material world. The following story is told to illustrate the point:

“A wealthy man once came to visit a man who was a great teacher and sage in Israel. He was shocked to find the teacher living in a sparsely furnished shack, run-down and uncomfortable and on the edge of town. The wealthy benefactor offered to build a home for the teacher that would be much more in keeping with his station in life.

“In reply, the teacher asked the man to describe his home and then to describe the accommodations he used while traveling. The wealthy man revealed that his home was in fact a huge mansion while he stayed in much more modest places while journeying.

“’I see,’ said the teacher. ‘And it is the same with me. I am but a sojourner on this earth and my accommodations are simple. But someday, I will dwell in my true home which is indeed a glorious mansion.'”

The sukkah also reminds God’s people of their total dependence on Him. No matter how sturdy our structures might seem, they offer no protection outside of God’s care. It is said that when a man sits in the sukkah of the shadow of faith, God’s presence is spread over him from above. It is God’s presence, His care, His protection and His provision that keep His people safe.

ChamelionsEye/shutterstock.com

The sukkah reminds the Jewish people of the importance of tikun olam, or repairing the world. It must never be forgotten that every act of kindness, every good deed done to a fellow man, makes the world a better place. Charity is also brought to mind by the sukkah. No matter how modest our circumstances might be, the rabbis say, there are always those who are worse off and in need of our giving.

The myriad of other lessons of Sukkot combine to become, in fact, weapons. The last day of the holiday ends with a verse from Isaiah: “No weapon that is formed against you shall succeed” (Isa. 57:17a HCSB). As the Jewish people prepare to leave the sanctity of this season, they are refreshed and renewed, armed for the battles of life with the many lessons they have learned and re-learned. Thus, the rabbis say, the real accomplishment of Sukkot is victory.

The eighth day of the Sukkot holiday in the Diaspora is called Shemini Atzeret. Shemini is the Hebrew word for eighth while atzeret has several meanings including assembly. It is a time of great rejoicing and its importance is summed up in a lovely story from the Jewish sages:

“There was once a king who invited his children for a banquet of several days. They laughed and sang, ate and danced together, reveling in their love for one another and their father’s love for them. When it came time for them to make their way home, the king stood and said, ‘My children, please, your parting is so difficult for me, please stay with me one more day…'”

It is important to note that the king does not refer to their separation as “our” parting, but rather “your” parting. We are reminded that God is everywhere and never parts from us. But as the Jewish people return to the cares and activities of life, they run the risk of parting from Him. And so He invites His beloved children to stay one more day, a day when sitting in the sukkah is a choice and not a mandate, a day to be further strengthened for the weeks and months to come.

The final day of the fall holidays is Simchat Torah. Meaning “joy of the Torah,” this day is the summation of all that has happened in the lives of the Jewish people for the past 60 days. It is the only day of the entire holiday season that is focused entirely on the Word of God. On this day, the Torah reading cycle for the year comes to an end, and immediately, it is re-started for the new year.

But the essence of the day goes far beyond the reading cycle. All of the joy of the past weeks, all of the lessons learned, all of the beautiful connections made with God, all of the weapons that were formed to bring victory in the coming year…all are found in the Torah. Like a photo album made with words, everything is there to be re-examined throughout the days ahead.

It is a day when the exultation of the Temple service is in a small measure recreated. Today, the Torah scrolls are removed from their home in the ark and an amazing dance begins. Round and round the sanctuary the dancers twirl, embracing the scrolls as others reach out to touch or kiss them on their way by. It is a dance of passion and immeasurable joy. It is called the “Dance of the Essence,” based on the verse that is recited immediately before the dance begins. “You in Your absolute essence have revealed Yourself so that we may know You.” Simon Jacobson sums it up this way:

ChamelionsEye/shutterstock.com

“We dance with each other and with God. We dance and celebrate the very essence of life and the gifts God has given us. After all the outpouring of prayer during this month, all the different expressions of awe and love—it all comes down to an unadulterated celebration of dance and song that expresses most our absolute passion and connection with God.”

Today, there are thousands if not millions of Christians around the world who are discovering the beauty and importance of the biblical holidays, exploring ways to celebrate them while respecting our Hebraic foundations and honoring our Christianity at the same time. It is no longer uncommon to find churches or Christian homes where a sukkah has been built, or to find Christians eating apples and honey on Rosh HaShanah. You may even discover them dancing with their Bibles on Simchat Torah.

blueeyes/shutterstock.com

Such connections are a gift that God is giving the Church in these incredible days in which we are living. All of those outward expressions are appropriate and even enjoyable. But more important are the inward lessons. We hope that this year’s journey from Elul to Simchat Torah has been an encouragement, not only helping to bridge the gap of understanding that often exists between Christians and our Jewish friends; but further helping us to desire the deeper meaning of this sacred time of year; to appreciate every moed that God has ordained for His people; to walk always in the presence of the Lord, grateful for our “instant access,” but aware that preparation for a special meeting with the King is very important. We pray that repentance will become a true hallmark of our lives, drawing us near and compelling us to dive headlong into the bottomless ocean of love that is our Beloved.

Jacobson, Simon. 60 Days, a Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays. New York:

Kiyum Press, 2008.

Kitov, Eliyahu. The Book of Our Heritage, (Vol. 1) Tishrei, Shevat. Jerusalem:

Feldheim Publishers, 1997.

Richman, Chaim. The Holy Temple of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Carta, 1997.

Yosef, Rabbi Mordechai. Living Waters. New Jersey: Jason Aronson Inc., 2001.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.