by: Rev. Terry Mason, Director of International Development

Having grown up in a Protestant Christian background, Wesleyan to be precise, I had no practical experience with priests and the concept of a “priesthood.” I had a vague sense of priests being men who eschewed marital relations in order to more fully pursue service to God. But recently, when I studied the weekly Torah (Gen.–Deut.) portion named Tetzaveh (You shall command), it really made me think. The portion covers Exodus 27:20–30:10 and is known as Parshat Cohanim, the portion of the priests. There is a lot involved in being priests. God called on all the Israelites to be “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” unto Him (Exod. 19:6). He also set apart the tribe of Levi for special service. As Christians who follow the one true God, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, we also understand that our calling is to serve Him, to join with the Jewish people in being a light to the nations by teaching God’s compassionate righteousness and moral justice. We do not replace them, but rather we join them in advancing God’s kingdom on earth.

Studying this particular passage reminded me of how the apostle Peter calls us a chosen generation and a royal priesthood. In 1 Peter 2:9 we read, “But you are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, His own special people, that you may proclaim the praises of Him who called you out of darkness into His marvelous light.” Do you embrace that calling to be “a royal priesthood?” It is a high calling indeed. As Christians we understand that Peter was writing to both Jewish and Gentile believers when he used the word “you” in the above designation. This is evident from his reminder in the next verse (v. 10) that once the Gentiles “were not a people” but now they are joining with the people of God. He also says that their past lives were lived in the sinful lusts of the Gentiles (1 Pet. 4:3–4 NASB). Being part of this royal priesthood and holy nation is therefore the calling of all true believers, both Jewish and Christian.

In our modern Christian constructs we have the notion of a “priesthood of all believers.” It was a central tenet of the Protestant Reformation. In his overview of the Protestant faith, J. Leslie Dunstan defines the concept, “The Reformers spoke about ‘the priesthood of all believers,’ meaning that each individual was both a priest for himself and for his fellow man. That is, every individual was able to deal directly with God, or God would deal directly with him without the mediation of any earthly organization.” He goes on to bemoan the fact that while the phrase is often repeated as a core principle of Protestant theology, the Church has done little to clarify what the phrase actually means. Consequently, I believe that the vast majority of Christians today do not understand their biblical mandate to serve the God of the universe as royal and holy priests. What practicality does the role of priest entail for the general Christian believer? How did this critically important tenet of faith become so obscured?

In the centuries since the Reformation, the Church developed a structural hierarchy in which a professional clergy developed. While this was necessary to some degree to preserve order and ensure “pure” preaching of truth, it served to undermine the ministry role of laypeople. “Contrary to the theory of fundamental non-distinction, it encouraged the practical recognition of a secondary status of the ‘laity’ in comparison with the ministry, the breeding of an attitude of passivity in the laity as a whole, the accentuation of the significance of ‘office’ and its leadership.” Yet Timothy George explains that for the Reformers, “the priesthood of all believers was not only a spiritual privilege but a moral obligation and a personal vocation… In other words, the priesthood of believers is not a prerogative on which we can rest; it is a commission which sends us forth into the world to exercise a priestly ministry not for ourselves, but for others.” George points out that it “did not mean, ‘I am my own priest.’ It meant rather: In the community of saints, God has so tempered the body that we are all priests to each other. We stand before God and intercede for one another, we proclaim God’s Word to one another and we celebrate His presence among us in worship, praise, and fellowship. Moreover, our priestly ministry does not terminate upon ourselves. It propels us into the world in service and witness.”

Let’s look more closely at the portion of scripture mentioned above, namely Tetzaveh or Exodus 27:20–30:10. Rabbi Shlomo Riskin points out that this is the first portion since the beginning of Exodus in which Moses’s name does not appear, while Aaron’s name is used over 30 times. While we read Moses’s name in the first sentence of the next portion, in this one he is completely absent. Seven weekly Torah (Gen.–Deut.) portions covering 27 chapters have dealt with the mighty prophet Moses: Moses who spoke for God, initiated great

Let’s look more closely at the portion of scripture mentioned above, namely Tetzaveh or Exodus 27:20–30:10. Rabbi Shlomo Riskin points out that this is the first portion since the beginning of Exodus in which Moses’s name does not appear, while Aaron’s name is used over 30 times. While we read Moses’s name in the first sentence of the next portion, in this one he is completely absent. Seven weekly Torah (Gen.–Deut.) portions covering 27 chapters have dealt with the mighty prophet Moses: Moses who spoke for God, initiated great  plagues and spoke directly with God on the fiery mountain. We read again and again, “God spoke to Moses saying…” In fact, Moses’s name is used about 153 times in Exodus 2–27, an average of almost six mentions per chapter. So we could expect to see his name in this weekly section around 16 times. But for three chapters his name is not used, only the personal pronoun “you.” When we see something unusual like this in the text, it is important to ask why.

plagues and spoke directly with God on the fiery mountain. We read again and again, “God spoke to Moses saying…” In fact, Moses’s name is used about 153 times in Exodus 2–27, an average of almost six mentions per chapter. So we could expect to see his name in this weekly section around 16 times. But for three chapters his name is not used, only the personal pronoun “you.” When we see something unusual like this in the text, it is important to ask why.

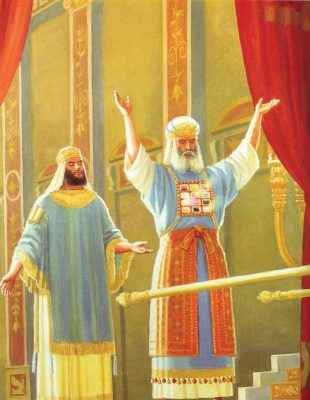

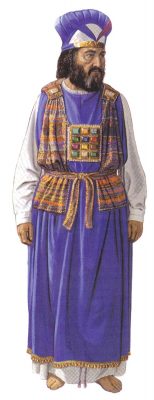

Perhaps God was trying to make a point. In fact, God explicitly tells Moses repeatedly that his brother Aaron and his sons would be the priesthood for the nation of Israel, not Moses and his sons after him. In Exodus 28:1 we read, “Now take Aaron your brother, and his sons with him, from among the children of Israel, that he may minister to Me as priest…” “From among” has the connotation of being separated out from the people of Israel to consecrate or make holy. Then in Exodus 29:9 we read, “And you shall gird them with sashes, Aaron and his sons, and put the hats on them. The priesthood shall be theirs for a perpetual statute.”

Perhaps God was trying to make a point. In fact, God explicitly tells Moses repeatedly that his brother Aaron and his sons would be the priesthood for the nation of Israel, not Moses and his sons after him. In Exodus 28:1 we read, “Now take Aaron your brother, and his sons with him, from among the children of Israel, that he may minister to Me as priest…” “From among” has the connotation of being separated out from the people of Israel to consecrate or make holy. Then in Exodus 29:9 we read, “And you shall gird them with sashes, Aaron and his sons, and put the hats on them. The priesthood shall be theirs for a perpetual statute.”

Obviously, the role of priest is very special and God only calls certain people into that position of service. Right?

In the Writings of the Apostles (NT), Paul tells us in 1 Corinthians 12 that within the Church some have been appointed prophets, teachers, apostles and so forth. Only some were called to be prophets, but apparently, according to several passages of Scripture, all true believers are called to be priests. Even in biblical times this was true. In Exodus 19:6 God speaks about the entire nation of Israel and says, “‘And you shall be to Me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation.’ These are the words which you shall speak to the children of Israel.”

While the tribe of Levi was singled out for particular service before God in the Tabernacle, all Israelites were meant to be priests as a light to the nations. This is where Peter picked up his language concerning those in the first century who, by faith, were believing in the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Again, the priesthood is a high calling indeed, and all who follow God are called into it. So let’s find out what that means and how to do it.

When trying to define something it can be helpful to know what it is not. A priest is not necessarily a prophet, though some of the biblical prophets did come from the priestly line. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks lists ten key differences between the biblical roles of prophet and priest.

When trying to define something it can be helpful to know what it is not. A priest is not necessarily a prophet, though some of the biblical prophets did come from the priestly line. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks lists ten key differences between the biblical roles of prophet and priest.

In biblical times, the priesthood was seen as the intermediary between God and the people of Israel, particularly in relation to the Tabernacle and later the Temple. But the priests also served other roles that varied over time:

In biblical times, the priesthood was seen as the intermediary between God and the people of Israel, particularly in relation to the Tabernacle and later the Temple. But the priests also served other roles that varied over time:

Judging role: Deuteronomy 17:9 says, “And you shall come to the priests, the Levites, and to the judge there in those days, and inquire of them; they shall pronounce upon you the sentence of judgment.”

Teaching role: Deuteronomy 33:10 says, “They [the Levites] shall teach Jacob Your judgments, and Israel Your law. They shall put incense before You, and a whole burnt sacrifice on Your altar.” The prophet Malachi wrote, “For the lips of a priest should keep knowledge, and people should seek the law from his mouth; for he is the messenger of the LORD of hosts” (Mal. 2:7).

Blessing role: Numbers 6:23 says, “Speak to Aaron and his sons, saying, ‘This is the way you shall bless the children of Israel.’” This is where we get the famous Aaronic blessing: “The LORD bless you and keep you; the LORD make His face shine upon you, and be gracious to you; the LORD lift up His countenance upon you, and give you peace” (vv. 24–26).

Clearly, according to Paul and the roles we just listed, we are not all called to be prophets. But we are all called to be priests. Honestly, when reading through the above roles, I more naturally identify with many of the characteristics of prophets than those of the priesthood. Perhaps the same is true for you. So, what to do if we identify more with the role of prophet but understand that we are called to be priests of the most high God?

Though it is a core doctrine of Protestant Christianity—well documented in the Writings of the Apostles (NT)—if I was to go into most churches and ask people to define what the “priesthood of all believers” means, I believe that few would be able to give a solid answer. Not all priests served the same functions, but we must attempt to serve in the role that God puts before us. So how do we realistically serve God as part of the “priesthood of believers?”

There are several things that we all must do. One is to “proclaim the praises of Him who called you out of darkness into His marvelous light” (1 Pet. 2:9). Hebrews 13:15 admonishes us to “continually offer the sacrifice of praise to God, that is, the fruit of our lips, giving thanks to His name.” Paul’s well-known admonition in Romans 12:1 says, “Therefore I urge you, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies a living and holy sacrifice, acceptable to God, which is your spiritual service of worship” (NASB). We also need to intercede for others. Just as the high priest bore the names of the Twelve Tribes on his shoulders and breastplate, we can draw near to God on behalf of others.

Then there are roles that we may be asked to fulfill as priests specific to us as individuals or for a certain time. We may be called to judge between right and wrong, help maintain the boundary of our faith, teach others who are younger in the faith, bless others in the name of our Father and King or give and share as we read in Hebrews 13:16, “But do not forget to do good and to share, for with such sacrifices God is well pleased.”

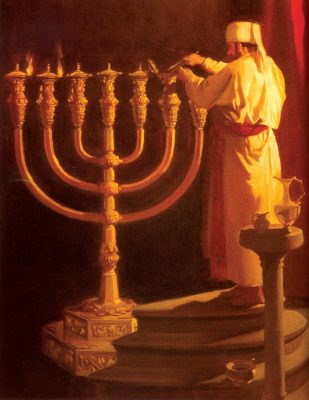

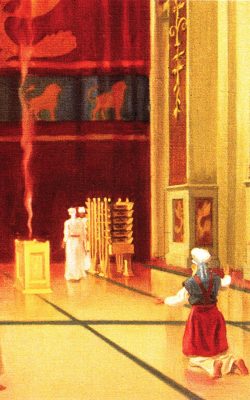

While the portion Tetzaveh (Exod. 27:20–30:10), which we discussed above, is known as the portion of the priests, Leviticus gives us an entire book focused in great detail on priestly service in the Tabernacle. Many people struggle to connect with this book. They say it seems outdated and deals with minutia that is no longer relevant to a believer’s life today. But we can actually learn a great deal about our role as priests in God’s kingdom by looking at Leviticus. Rabbi Shai Held explains in his commentary on Leviticus, “The tabernacle (mishkan) is nothing if not a tightly structured, highly ordered space. Who may enter where, at what time, and in what garb—all is tightly regulated. The profane must never spill over into and thus violate the sacred. The sacrifices are carefully choreographed and presented ‘just right.’ In a chaotic, terrifying world, one place, at least, is governed by order and structure.”

In much of today’s world, a high value is placed on free choice or being able to do as one pleases. This ideal has crept into the lifestyles that many Christians lead. Arguably the consequence of this value is a lack of order, which causes many to live with a sense of anxiety. I believe that one major key to our role as priests is to create a place of order in the world, both for ourselves and others. We are to create a counter reality, if you will, in an otherwise chaotic world, a counterworld which “holds out the gift of a well-ordered, joy-filled, and peace generating creation” as God intended.

Rabbi Held points out the connection between God’s creation of the world and the priestly service in the Tabernacle. “How does God bring about a habitable world? By dividing, separating, and ordering—and then bringing forth life.” God separates the light from the darkness, the waters above from the waters below, the sea from the dry land. He places lights in the firmament to distinguish day from night. Then God sets apart the Sabbath from other days and calls it holy. Likewise, Leviticus teaches about dividing animals between those that are clean and those that are unclean. It goes into great detail about physical relationships that are allowed and those that are forbidden. When Israel as a people separates permitted and forbidden things, they are following God’s example and walking after Him. Leviticus 20:26 tells them why they are to separate and make distinctions, “And you shall be holy to Me, for I the LORD am holy, and have separated you from the peoples, that you should be Mine.”

For Christians, this should remind us of the challenging command Jesus (Yeshua) gave in Matthew 5:48, “Therefore you shall be perfect, just as your Father in heaven is perfect.” We are all called to lead holy lives. “…but as He who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct…” (1 Pet. 1:15). It is clear from the Writings of the Apostles (NT) that we are called to separate ourselves from worldly ways. For example, Paul admonishes in Romans 12:2, “And do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind, that you may prove what is that good and acceptable and perfect will of God.” In Ephesians 4:22–24 Paul says, “…put off, concerning your former conduct, the old man which grows corrupt according to the deceitful lusts, and be renewed in the spirit of your mind, and that you put on the new man which was created according to God, in true righteousness and holiness.”

As priests serving the holy God, we are expected to be holy people reflecting His righteousness, peace and joy to the world. One important way that we can do this is by following God’s example to divide, separate and bring order. We can walk in the light as He is in the light and tactfully call darkness what it is. We can let our light shine before men in such a way that they will glorify our Father in heaven (Matt. 5:16). From the beginning of Genesis onwards, all who believe in the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob are intended to be His agents in the world, bringing order and creating a society that follows His good plans for living. By taking up our roles as priests in His kingdom, we can do just that.

Dunstan, Leslie J. Protestantism. New York: George Braziller, 1962.

George, Timothy. “The Priesthood of all Believers.” First Things. https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2016/10/the-priesthood-of-all-believers

Held, Shai. The Heart of Torah (Vol 2). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

New American Standard Bible, The Open Bible Edition. Multiple Editors and Contributors to the Bible Study Helps and Biblical Information Content. USA: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1976.

Riskin, Shlomo. Torah Lights: Shemot: Defining a Nation. Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2009.

Sacks, Jonathan. Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible. Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2015.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.