×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Rev. Nathan Williams, Director of Marketing and Communications

Life can be tough. We only have to look back over the last two years of life on planet Earth to realize that circumstances in this world can overwhelm us. Loss, sickness, uncertainty, pain and oppression will inevitably come upon us as we navigate through this fallen world. As believers in Jesus (Yeshua), we are not promised a problem-free life. On the contrary, we are assured that life might be tough for us. We are, however, assured that we need not be troubled by the adversity that we face, as Jesus has overcome the world (John 16:33).

As we attempt in our limited human understanding to reconcile the omnipotent, omnipresent and omniscient aspects of the character of God, we find ourselves searching for answers to some of life’s most difficult questions. Oftentimes we cry out to the Lord for understanding of our circumstances and events that leave us bewildered. The ultimate question is: If we do not receive an explanation for every awful experience, can we continue to sustain our belief in the Lord?

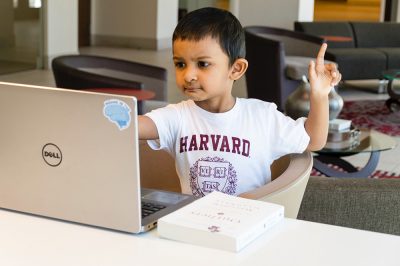

According to a recent study in the United Kingdom compiled by child psychologist Dr. Sam Wass, children ask an average of 73 questions each day. When the study specifically looked at the four-year-old age group, the daily number of questions exploded to 200–300 questions per day. In fact, the study concludes that parents are asked more questions per hour than primary-school teachers, doctors and nurses combined. Each of us can probably remember a time during our schooling career when we were taught the five “W’s”: who, what, where, when and why. These questions encourage critical thinking and help us understand situation and context.

The drive for explanation is not a taught behavior. It is, as the study above recognizes, an innate desire for explanation that manifests even in early childhood development. Asking why expresses a desire to understand the world around us, and understanding brought about by an answered question increases security and confidence. The ability to ask questions is an important part of childhood development and a learning process which continues throughout our lives. We ask questions because we lack information we need, something simple, like: What is the time? We use questions as icebreakers in new social settings and as conversation starters. Some questions have definite answers while other questions are more difficult to answer.

“How are you?” is such a simple question ingrained in our social interactions, yet it can be a difficult question to answer. This question challenges us to first evaluate the motives of the asker. Does this person really want to know how I am doing, or are they just being polite? We then have to decide whether to answer truthfully or with a simple platitude. As Christians, there is unspoken pressure at times when we can’t say that we are having a bad day, as if our negativity somehow discredits God’s care and provision for us. This pressure is even more intense when it comes to questioning and attempting to understand the trials and tribulations of life. After all, God is omnipotent, omnipresent and omniscient—so our expectation is that He should honestly answer all of life’s difficult questions.

“How are you?” is such a simple question ingrained in our social interactions, yet it can be a difficult question to answer. This question challenges us to first evaluate the motives of the asker. Does this person really want to know how I am doing, or are they just being polite? We then have to decide whether to answer truthfully or with a simple platitude. As Christians, there is unspoken pressure at times when we can’t say that we are having a bad day, as if our negativity somehow discredits God’s care and provision for us. This pressure is even more intense when it comes to questioning and attempting to understand the trials and tribulations of life. After all, God is omnipotent, omnipresent and omniscient—so our expectation is that He should honestly answer all of life’s difficult questions.

This desire is not unique to us modern-day Christians but can be traced all the way back to the beginning of our faith. “The heroes of faith asked questions of God,” writes Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, “and the greater the prophet, the harder the question. Abraham asked, ‘Shall the judge of all the earth not do justice?’ Moses asked, ‘O Lord, why have You brought trouble upon this people?’ Jeremiah said, ‘You are always righteous, O Lord, when I bring a case before You, yet I would speak with You about Your justice: Why does the way of the wicked prosper? Why do all the faithless live at ease?’” These are indeed some of life’s difficult questions.

The book of Job is an amazing exposition of man trying to understand the problem of human suffering. It is a book of questions asked by a human during the most trying time of his life, and of him trying to find answers from a human perspective about why these terrible things are happening to him. Job struggles with one of the most difficult questions: Why do the righteous suffer? Initially, after the loss of riches and the death of his children, Job displays remarkable resilience. “The LORD gave, and the LORD has taken away; blessed be the name of the LORD” (Job 1:21b). However, Job’s suffering does not end there, and as months of living in agony with a loathsome disease are added to his loss, his resolve starts to wear thin.

In chapter three, Job begins to ask why and does so seven times in that chapter. Why, wonders Job, must he be kept alive for what he experiences as a living death? Job and his friends conjure up a mistaken theology that suffering is the result of personal sin—and if not, then the problem must lie with the Lord, that His divine justice is not being administered fairly. Job declares: “The earth is given into the hand of the wicked. He covers the faces of its judges. If it is not He, who else could it be?” (Job 9:24). Job alleges that surely God has turned his back on the iniquity of the wicked, as they seem to prosper, and if these injustices are not the Lord’s fault, who else can be held responsible?

Gam zu le’tovah is a Hebrew expression that translates roughly to “this too, is for the good.” “This” refers to the trial or suffering that a person is enduring. In Jewish thought, it is the idea that even though we do not understand why bad things happen to us, we can trust that even the negative things happen according to God’s will. It is a perspective that is meant to be comforting, the idea that we do not have the full perspective when misery hits, and that we should trust that all events, whether good or bad, will in the end be for good. But does this ring true even in the face of horrific loss?

Gam zu le’tovah is a Hebrew expression that translates roughly to “this too, is for the good.” “This” refers to the trial or suffering that a person is enduring. In Jewish thought, it is the idea that even though we do not understand why bad things happen to us, we can trust that even the negative things happen according to God’s will. It is a perspective that is meant to be comforting, the idea that we do not have the full perspective when misery hits, and that we should trust that all events, whether good or bad, will in the end be for good. But does this ring true even in the face of horrific loss?

In her memoir, The Blessing of a Broken Heart, longtime friend of Bridges for Peace, Sherri Mandell, writes about the horrific loss of her son, Koby, and her journey towards healing and light. Koby and his friend, Yosef, skipped school one day to go hiking in the Judean Wilderness. A day later, their brutally murdered bodies were found in a cave. “Why was Koby chosen? Why were we?” writes Mandell. “Even Job, the righteous man, could not contain himself and questioned God, railing against his suffering.” Understandably, Mandell acknowledges that she struggles to accept the concept of gam zu le’tovah in the light of her severe loss. “Having your son stoned to death by Palestinian terrorists doesn’t seem like the kind of thing to which one can say: ‘Gam zu le’tovah.’ I will never say that my son’s death is good…though I have to believe that God has a plan, even if this plan hurts us.”

Rabbi Eliezer Parkoff asserts that if we, like Job’s first three friends, merely look at things intellectually, we are at risk of creating a skewed theology and arguing a flawed case against God. In our intellectual reasoning, we would be missing a dimension of the argument: “Ultimately what is required of us is simple faith,” writes Rabbi Parkoff. “Yes, we are encouraged to use our minds to the fullest understanding. We are charged to approach such problems with the deepest thinking possible. However, the basic underlying foundation of all our understanding must be simple emunah (faith).” And this is the same conclusion that Mandell reached: “I have to believe that God has a plan.”

Questioning God is not evil in and of itself. We find an excellent example of grappling through questioning the providence of God in the book of Habakkuk, who prophesied of the coming destruction of Judah at the hands of the Babylonians and wanted to know why the Lord would use a wicked nation like Babylon to punish Judah (Hab. 1:12–17). Rather foolhardily, Habakkuk demands an answer from God (Hab. 2:1). The Lord answers Habakkuk with certainty on His plan for the punishment of Judah and urges the impulsive prophet of his need for humility and faith (Hab. 2:4). As the Lord continues explaining to Habakkuk, He concludes that all men would do well to keep silent before Him and not question His wisdom and justice (Hab. 2:20). Although this is a strong rebuke, the Lord goes on to reveal to Habakkuk the glorious plan of salvation for His faithful ones and the destruction of their enemies. Habakkuk finishes by affirming his faith in the wisdom and final victory of the Lord (Hab. 3:17–19).

As Rabbi Sacks says—and Habakkuk experienced: “To ask is to grow.” Doubt and unbelief can be sinful, but earnestly seeking understanding from the Lord is not. Asking questions that defame the character of God or questioning His sovereignty from a rebellious, prideful heart are definitely problematic. The Lord is not intimidated by our questions, and in fact, He desires a real relationship with us. Just as children in their formative years question to gain understanding and increase their security and confidence, so I believe the Lord invites us to grow in this way in our relationship with Him. Our main concern should be whether we are coming in faith or unbelief—and that our heart attitude is pure, which the Lord clearly sees.

We have discovered that we are at liberty to ask questions of God within certain parameters, but that does not mean the Lord will always answer our questions, or in the way that we expect. The Lord expects us to trust Him, and that can be a difficult part of our walk of faith. Our obedience should not be reserved until we understand exactly what He is doing and asking us to do. There is a part of our journey of faith here on earth that is learning to become childlike, not just in asking questions, but also in childlike faith. Like a child who has to be satisfied with their parent’s simple answer of “because” to their incessant “why” questions, so we need to be childlike in our acceptance of things that we do not understand—knowing, trusting, believing that the living God is working things out for our good, according to His riches in glory.

We have discovered that we are at liberty to ask questions of God within certain parameters, but that does not mean the Lord will always answer our questions, or in the way that we expect. The Lord expects us to trust Him, and that can be a difficult part of our walk of faith. Our obedience should not be reserved until we understand exactly what He is doing and asking us to do. There is a part of our journey of faith here on earth that is learning to become childlike, not just in asking questions, but also in childlike faith. Like a child who has to be satisfied with their parent’s simple answer of “because” to their incessant “why” questions, so we need to be childlike in our acceptance of things that we do not understand—knowing, trusting, believing that the living God is working things out for our good, according to His riches in glory.

The apostle Paul understood the human desire to question, to understand, to cry out to the Lord for answers in our trials. So take courage in the midst of your trials with the words from Paul’s epistle to the Romans, encouraging us with the promise of future glory, that nothing can separate us from the love of God: “And we know that all things work together for good to those who love God, to those who are the called according to His purpose” (Rom. 8:28).

Elsworthy, Emma. “Kids Ask a Staggering 73 Questions Every Day—Half of Which Mums and Dads Struggle to Answer.” SWNS Digital. Accessed December 2021. https://swnsdigital.com/uk/2017/12/kids-ask-a-staggering-73-questions-every-day-half-of-which-mums-and-dads-struggle-to-answer/

Mackey, Eleanor. “Why Do Toddlers Ask Why?” Rise and Shine. Accessed December 2021. https://riseandshine.childrensnational.org/why-do-toddlers-ask-why/

Mandell, Sherri. The Blessing of a Broken Heart. London: The Toby Press, 2003. pp. 41, 168–169.

Parkoff, Rabbi Eliezer. Fine Lines of Faith. Jerusalem/New York: Feldheim Publishers, 1994. dp.5.

Sacks, Rabbi Lord Jonathan. Haggadah: Hebrew and English Text with New Essays and Commentary. Jerusalem, Maggid Books, 2015. pp. 106-108

Skenazy, Lenore. God Gave Us Lemons for a Reason. Accessed December 2021. https://forward.com/articles/153004/god-gave-us-lemons-for-a-reason/

“What Were the Questions that Habakkuk Asked God?” Bible Ask. Accessed December 2021.https://bibleask.org/questions-habakkuk-asked-god/

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.