×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Rev. Cheryl L. Hauer, International Vice President

In the ancient world, prior to our story of Joseph, forgiveness was an unknown concept. Experts in the writings and social customs of ancient civilizations agree that true forgiveness did not exist prior to Joseph’s remarkable act of mercy. Ancients certainly had societal norms that made existing with one who had wronged them possible, but those processes were not forgiveness. Appeasement through which the guilty party found a way to satisfy the anger of the one they had wronged was the norm. Money, material goods and even servitude were means by which an injured party could be moved to give up his or her right to vengeance and live in peace, if not harmony. According to Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, humanity changed the day Joseph forgave his brothers. It was the first recorded moment in history in which one human actually forgave another.

It is no wonder the brothers grew fearful after the death of their father. They had appeased Joseph by reuniting him with the father and younger brother he so dearly loved—but forgiveness? How could they even comprehend such a thing? Regardless of the part each one had played, they were all complicit and forced to support one another in the story they created to tell their father. Filled with bitterness and steeped in their own unforgiveness, they had taken pleasure in tearing apart Joseph’s soft, woolen chieftain’s cloak and drenching it in the blood of goats. One must wonder what satisfaction some felt, if any, in watching as their father’s life and dreams crumbled in an instant—perhaps sweet revenge for years of being forced to live in Joseph’s shadow. His beloved son gone, no words of consolation could ever be enough to lessen Jacob’s grief. He was a devastated, broken man and would never be the same. But God had a plan to elevate humankind by introducing repentance and forgiveness into the human condition. No longer would it be necessary for man to remain a prisoner of his past.

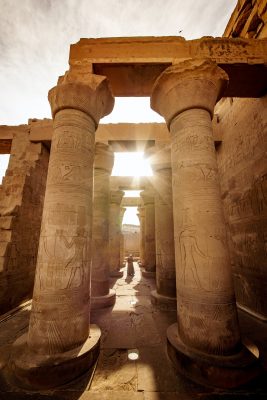

The journey to that forgiveness, however, was not an easy one. Once in Egypt, Joseph continually “floated to the top,” recognized for his intelligence, integrity and leadership skills. As a slave, he became administrator of the household; as a prisoner, the overseer of the other inmates; and then, as an interpreter of dreams, became the governor of all Egypt. As second-in-command to Pharaoh, he found himself in control of the entire food system of the country during a time of region-wide famine. Regardless of his successes, however, it is difficult to imagine a day on which Joseph would not have thought of his father, felt the sadness of betrayal and wondered what might have been had his brothers been able to forgive him as he was striving to forgive them. Yet through it all, he remained a man of integrity, his character shaped and informed by his strong faith in God.

The journey to that forgiveness, however, was not an easy one. Once in Egypt, Joseph continually “floated to the top,” recognized for his intelligence, integrity and leadership skills. As a slave, he became administrator of the household; as a prisoner, the overseer of the other inmates; and then, as an interpreter of dreams, became the governor of all Egypt. As second-in-command to Pharaoh, he found himself in control of the entire food system of the country during a time of region-wide famine. Regardless of his successes, however, it is difficult to imagine a day on which Joseph would not have thought of his father, felt the sadness of betrayal and wondered what might have been had his brothers been able to forgive him as he was striving to forgive them. Yet through it all, he remained a man of integrity, his character shaped and informed by his strong faith in God.

Although the word “forgiveness” does not appear anywhere in the biblical narrative, the concept is at the heart of Joseph’s story. Nowhere in it does God accuse him or point out a sin or a failing on his part, even though he had every reason to become a bitter, angry man. He was, after all, the poster child for familial abuse. He was hated by those who should have loved him, betrayed, enslaved, imprisoned, forgotten, ignored and falsely accused. Joseph’s unshakable belief, however, in the sovereignty of the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob was the foundation from which he could pardon the iniquities of others and let go of the offenses committed against him.

It is conceivable, even likely, that his father, Jacob, taught him of the prophecy God had spoken to his great-grandfather Abraham (Abram): “Then He said to Abram: ‘Know certainly that your descendants will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and will serve them, and they will afflict them four hundred years. And also the nation whom they serve I will judge; afterward they shall come out with great possessions’” (Gen. 15:13–14).

Perhaps Joseph recognized the role that God had chosen for him to play in the eventual fulfillment of this prophecy. Jacob and his entire family were now in Egypt and would remain there, eventually enslaved, for 400 years—just as God had said. It was a realization that made it possible for him to say to his brothers: “And God sent me before you to preserve a posterity for you in the earth, and to save your lives by a great deliverance. So now it was not you who sent me here, but God” (Gen. 45:7–8a).

It is important to understand that God did not create Joseph’s negative circumstances, nor did he condone the abuse that Joseph suffered. But He was able to use those situations to mold Joseph into the man of strength, courage and integrity that God intended Him to be. Joseph was 17 when his brothers sold him and 30 when he appeared before Pharaoh. For the better part of thirty years, he suffered at the hands of those around him, yet his faith in God and his trust in God’s love and steadfastness never wavered.

Joseph recognized that forgiving his brothers was a necessary component of an obedient life. He could have succumbed to the temptation to live as a perpetual victim as we sometimes do. He might even have been justified to wallow in a bit of self-pity from time to time. After all, he was a victim. Had he chosen to remain one, however, he would never have risen to the full potential God had for him.

That temptation is often there for us as well. We may have been hurt by those around us, by no fault of our own. Like Joseph, we have been victimized. But God’s message to us is clear: “Therefore, as the elect of God, holy and beloved, put on tender mercies, kindness, humility, meekness, longsuffering; bearing with one another, and forgiving one another, if anyone has a complaint against another; even as Christ forgave you, so you also must do” (Col. 3:12–13).

Failure to forgive is not without consequences either. If we want to walk in God’s forgiveness, it is essential that we extend that same forgiveness to those who have injured us. “And his master was angry, and delivered him to the torturers until he should pay all that was due to him. ‘So My heavenly Father also will do to you if each of you, from his heart, does not forgive his brother his trespasses’” (Matt. 18:34–35).

The Bible tells us that we are able to love because the Lord first loved us. The same is true of forgiveness, and that means forgiving often, as many times as it takes: “Then Peter came to Him and said, ‘Lord, how often shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive him? Up to seven times?’ Jesus said to him, ‘I do not say to you, up to seven times, but up to seventy times seven’” (Matt. 18:21–22).

When Jesus (Yeshua) spoke these words, the number seven stood for completeness, totality, the finished product. The phrase “70 x 7” then meant “without end.” In other words, true forgiveness has no boundaries. It is always there and available to whoever needs it.

When Jesus (Yeshua) spoke these words, the number seven stood for completeness, totality, the finished product. The phrase “70 x 7” then meant “without end.” In other words, true forgiveness has no boundaries. It is always there and available to whoever needs it.

Joseph had made the decision to forgive his brothers long before they appeared on the scene. It was a deliberate action on his part, forgiving those whom he thought he would never see again. But with their arrival in Egypt, the situation moved from forgiveness to reconciliation, reuniting and rebuilding a relationship. That required action on the part of his brothers.

In Genesis 42–44, we read of action on Joseph’s part, though very strange indeed. From hiding his brothers’ money in their own bags and hiding his own royal cup in their bags as well, to demanding that one of the brothers be left behind as surety for the others, he took extreme measures to determine whether or not his brothers were actually repentant of the sins they had committed against him. In ancient Israel, sincere repentance could only be seen when one was presented with similar circumstances and temptations, but the sin was not repeated. Clearly, he was satisfied that they painfully regretted their actions, and he was ready to welcome them into his life again.

It is important for us to remember that we can forgive those who have harmed us even though they have not repented. However, the belief that we should just forget those transgressions and blindly trust again is not biblically sound. Joseph walked in the freedom of forgiveness when his brothers were hundreds of miles away and thought he was dead. But he was not willing to freely trust them again until he was satisfied that they were, in fact, worthy of that trust.

It is important for us to remember that we can forgive those who have harmed us even though they have not repented. However, the belief that we should just forget those transgressions and blindly trust again is not biblically sound. Joseph walked in the freedom of forgiveness when his brothers were hundreds of miles away and thought he was dead. But he was not willing to freely trust them again until he was satisfied that they were, in fact, worthy of that trust.

God’s idea of forgiveness is one of permanence. Once He has extended it to us, it is ours and can’t be taken from us. However, for us as human beings, that isn’t so easy. Letting go of hurt and releasing our desire for payback, revenge or retaliation can take time. For us, it can be a process, which might mean forgiving every day—or even every hour—until at last, we have achieved that permanence. A mark of that achievement might be that we are finally able to pray for the restoration of the one who has offended us.

Joseph’s story is certainly one of total commitment to a godly life. Regardless of the actions of those around him and the effect those actions might have on his life, Joseph was committed to faithfully, constantly trust and serve God. His brothers believed they would never see him again but carried the burden of their guilt for many years. Joseph believed he would never see his family again, and though he was able to forgive his brothers, he must have endured great sadness because of his loss. Jacob believed he would never see his beloved son again and lived many years in a state of grief.

Joseph’s story is certainly one of total commitment to a godly life. Regardless of the actions of those around him and the effect those actions might have on his life, Joseph was committed to faithfully, constantly trust and serve God. His brothers believed they would never see him again but carried the burden of their guilt for many years. Joseph believed he would never see his family again, and though he was able to forgive his brothers, he must have endured great sadness because of his loss. Jacob believed he would never see his beloved son again and lived many years in a state of grief.

However, God had a plan to reunite this very dysfunctional family, to bring reconciliation and healing to all their wounded hearts. It was His desire to then bless them with years of a new kind of relationship based on trust and goodwill. The key to it all was Joseph’s ability to forgive, to recognize the sovereignty of God in his life, to let go of the pain of the past and move into a victorious future.

Through our relationship with the Lord, we, like Joseph, have the ability to walk in true forgiveness and victory, to let go of hurt and anger and trust Him with the future, to say to those who have wounded us: “…You meant evil against me; but God meant it for good…” (Gen. 50:20).

Photo Credit: Click on photo for photo credit

Konstan, David, Before Forgiveness: The Origins of a Moral Idea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Sacks, Rabbi Jonathan. “The Birth of Forgiveness (Vayigash 5775).” The Office of Rabbi Sacks. https://rabbisacks.org/birth-forgiveness-vayigash-5775/

Scripture is taken from the New King James Version, unless otherwise noted.

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.