×

We have detected your country as:

Please click here to go to the USA website or select another country from the dropdown list.

by: Abigail Gilbert, BFP Staff Writer

Every year on Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), the Jewish people read the book of Jonah as a study in true teshuvah (repentance). The brief account (only 48 verses long) highlights the importance of turning from wickedness back to the path of God, as illustrated by both Jonah and the people of Nineveh.

The book of Jonah is packed with lessons and principles—the fruitlessness of disobeying God, His readiness to accept true repentance, His concern for each soul, no matter its background, His patience and lovingkindness. Still, a major theme throughout the book is Jonah’s insistence and personal conviction that Nineveh should not have the chance to repent. Where did that resistance come from and what was God’s response? The answer to both questions is at the heart of the book of Jonah.

When the word of the Lord comes, it comes to Jonah, the son of Amittai. This isn’t the first time we’ve met Jonah in the Scriptures. In 2 Kings we hear that God “restored the territory of Israel from the entrance of Hamath to the Sea of the Arabah, according to the word of the Lord God of Israel, which He had spoken through His servant Jonah the son of Amittai, the prophet who was from Gath Hepher” (2 Kings 14:25). The Midrash (Jewish writings) says Jonah was known as a person of truth because his prophecy concerning the restoration of Israel’s borders under Jeroboam was explicitly fulfilled “from the entrance of Hamath to the Sea of the Arabah” (v. 25). Jeroboam was an evildoer in God’s eyes, his deeds described as “all the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, who had made Israel sin” (v. 24). 2 Kings 14 goes on to say God saved Israel from destruction because He saw their affliction, and He saw there was no help for them. He saved the people despite the evil done by an unrepentant king.

Jonah witnessed all this. He had a hand in it, bringing the good news of Israel’s restored borders. He saw the undeserved divine compassion God had on the sinful nation of Israel. When God called Jonah to go to the Assyrian capital, Nineveh, and demand repentance, Jonah disobeyed. He had seen God’s relentless mercy firsthand, and he knew if he brought the message of forgiveness to Israel’s enemies in the enormous city of Nineveh, he would likely see that mercy again.

When the Lord commands Jonah to go to Nineveh and “cry out against it” (Jon. 1:2), Jonah chooses to flee to Tarshish––in the opposite direction of Nineveh––rather than comply with an order he doesn’t believe in. Scripture says he fled “from the presence of the Lord” (Jon. 1:3), choosing distance from God rather than obedience. To understand such a drastic move from a seasoned prophet of God, we have to take a closer look at who exactly the Assyrians were and what their survival would mean for Israel.

When the Lord commands Jonah to go to Nineveh and “cry out against it” (Jon. 1:2), Jonah chooses to flee to Tarshish––in the opposite direction of Nineveh––rather than comply with an order he doesn’t believe in. Scripture says he fled “from the presence of the Lord” (Jon. 1:3), choosing distance from God rather than obedience. To understand such a drastic move from a seasoned prophet of God, we have to take a closer look at who exactly the Assyrians were and what their survival would mean for Israel.

The Assyrians were a particularly cruel enemy of the Israelites. They emerged as a territorial state in the 14th century BC, and by 9th century BC they’d consolidated their control over northern Mesopotamia. But that wasn’t enough for the bloodthirsty kingdom. They became a menace to smaller Syro-Palestinian states to the west, including Israel and Judah. We have extensive records of their conquests, engraved on stones and obelisks; many graphically describe the horrific tortures the Assyrians invented to punish the countries they conquered. The Assyrians’ cruelty made them a byword of fear among the nations.

Many scholars believe Jonah’s knowledge of Assyrian brutality could have come from personal experience—someone he knew, maybe even a family member, could have been killed in one of the invader’s infamous raids. Not only would God’s call to Nineveh place Jonah in real danger, but by telling the Ninevites of God’s impending wrath, Jonah was very likely providing an opportunity for the people he despised most to repent and escape destruction. Added to this agony was the insult that Jonah’s own people refused to listen to God’s message of repentance. Rebetzin Tziporah Heller sums it up well in her article “Jonah and the Whale:” “His own people were falling uncontrollably into a chasm that seemed to have no bottom, yet he was sent to save others—the archenemies of Israel!”

As a prophet, Jonah knew another byproduct of Nineveh’s repentance would be the eventual destruction his own homeland. As Rabbis Nosson and Slotowitz say in their anthology, Trei Asar: The Twelve Prophets, Jonah likely knew that if the Ninevites turned from their ways they would “become worthy of their later role as the ‘rod of God’s anger’ in becoming God’s instrument in later punishing Israel.” This added weight to his proclamation, essentially making Jonah the mouthpiece for his own nation’s coming destruction. So Jonah decided not to obey the word of the Lord, but though he fled the physical land of Israel, he soon found the God of Israel is not confined to man-made borders.

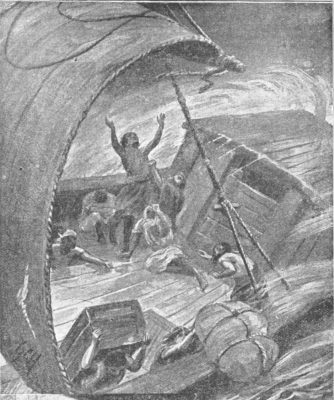

The book of Jonah is highly poetic. Throughout the book, we see the word “arise” referring to hearts and souls and principles moving toward God, and “descend” referring to those same things moving away from Him. From the moment Jonah chose to leave God’s presence, the author highlights Jonah’s downward path: “down to Joppa” and “down into the lowest parts of the ship;” even the word for sleep in Jonah 1:5, veyeradam (וירדם), is related to the Hebrew word yarad (ירד), the “go down” verb used previously in the chapter. On the other hand, the sailors cried for him to do the opposite, saying, “Arise, call on your God” (Jon. 1:6). Even when they threw Jonah into the sea the language is upward-focused, “they picked up Jonah.” Ironically, it is this “picking up” of Jonah and the subsequent tossing into the sea that ends up saving the sailors, as well as Jonah and the Ninevites.

The book of Jonah is highly poetic. Throughout the book, we see the word “arise” referring to hearts and souls and principles moving toward God, and “descend” referring to those same things moving away from Him. From the moment Jonah chose to leave God’s presence, the author highlights Jonah’s downward path: “down to Joppa” and “down into the lowest parts of the ship;” even the word for sleep in Jonah 1:5, veyeradam (וירדם), is related to the Hebrew word yarad (ירד), the “go down” verb used previously in the chapter. On the other hand, the sailors cried for him to do the opposite, saying, “Arise, call on your God” (Jon. 1:6). Even when they threw Jonah into the sea the language is upward-focused, “they picked up Jonah.” Ironically, it is this “picking up” of Jonah and the subsequent tossing into the sea that ends up saving the sailors, as well as Jonah and the Ninevites.

Even as heathens, the sailors’ actions appear more righteous than the disgraced servant of God. They call on God first, and when they learn that Jonah is a Hebrew who fears “the Lord, the God of heaven, who made the sea and the dry land” (Jon. 1:9), they are in awe and make the immediate connection between the storm and Jonah’s disobedience. When Jonah tells them to throw him into the sea, they still try to row to shore so that his blood will not be on their hands. After they feed him to the waves, they don’t forget what saved them. We read that they “feared the Lord exceedingly, and offered a sacrifice to the Lord and took vows” (Jon. 1:16). What a beautiful testament to God’s faithfulness here in the middle of this exciting tale. God shows genuine care and concern for these sailors who do not know His name, just as He will show concern for the heathen Ninevites, and His reluctant servant, Jonah.

The Lord “prepares” a great fish to swallow Jonah once he’s thrown into the waves (Jon. 1:17). Contrary to what you might have seen on your Sunday school felt board, the notion that the fish was a whale is baseless. The words גדול דג (dag gadol) are strictly translated “big fish,” and the reference to God’s divine intervention could mean this was a special fish or sea monster created only for Jonah. According to Trei Asar, “the identity of the species of the fish is unimportant and the attempt to identify it distracts us from the essential thread of our narrative. It suffices to mention that the verse emphasizes that this fish was prepared by God to act as His agent.”

After three days and nights within the belly of the fish, Jonah prays to God. His prayer is a psalm of worship and affliction. He cries out to the Lord “out of the belly of Sheol” and thanks the Lord for hearing his voice, for not leaving him in the deep with weeds wrapped around his head: “You have brought up my life from the pit, O Lord, my God. When my soul fainted within me, I remembered the Lord; and my prayer went up to You, into Your holy temple” (Jon. 2:6–7). Here Jonah repents, recognizing the Lord’s mercy, as he lifts his voice in thanksgiving and says, “I will pay what I have vowed” (Jon. 2:9).

We see here the foreshadowing of Nineveh’s repentance. Jonah recognized his wrongdoing when he first fled the Lord’s command, but here his recognition is paired with repentance. He’s yet to truly understand the heart of God for the people of Nineveh, but he acknowledges that his way has only led to the pit and the stinking belly of a great fish. He’s willing to try obedience, and it is at this point of recognition that the Lord tells the fish to vomit Jonah onto dry land. We see again the word “arise,” calling Jonah from his former downward path; and this time, Jonah agrees.

Ninevite folklore spoke of a god-like emissary who would come from the sea, linked with Dagon, the half-fish, semi-human idol of Assyria the Philistines once worshipped. Geoffrey Bull, in his book The City and the Sign, noted that while the book of Jonah never references this link, Jonah’s arrival from the “belly of the great fish” likely startled the pagan Ninevites more than we realize. It’s an interesting possibility, but all we know for sure is that when Jonah entered the vast city, his message was one of doom alone: “Yet forty days, and Nineveh shall be overthrown” (Jon. 3:4)! He offers no hope of salvation. With the likelihood of damnation and death looming on the horizon, the people of Nineveh choose to give up their wickedness and turn in repentance. Rabbi Baruch writes in “The Sign of Jonah” that the story of the reluctant prophet “reveals that the true repentance is not based on the promises of G-d, but the fact that there is One Holy and Righteous G-d Who is supreme and all people should serve Him because of Who He is and not what He offers.”

Because this book is read in its entirety during the Jewish observance of Yom Kippur, the themes of repentance in this chapter especially bear notice. The king of Nineveh calls for teshuvah through three main actions: stop, cry and turn. First we read that the king arose from his throne and laid aside his robe, decreeing: “let neither man nor beast, herd nor flock, taste anything; do not let them eat or drink water” (Jon. 3:7). Then he tells them to “cry mightily to God,” (v. 8) and after that “turn from his evil way and from the violence that is in his hands” (v. 8). This is a good model for us as believers when we are faced with recognition of our wrongdoing and need to repent. The king tells the people to stop their sinning, plus other lawful acts of life––eating, drinking, tending cattle. This fast forces men blinded by their sin to see the reality of the crisis. This cry to God is powerful because it involves belief and trust in God––the hope He will turn His hand from the city’s destruction. The “turn” is perhaps the most potent step of teshuvah––not just a turning “from,” but a turning “to.” It’s not enough to simply cease the sin. You must replace it with something of God.

Yom Kippur is a time for the Jewish people to move towards the will of God and the mission for which they were created—a sanctified time to repent of wrongdoing and return to God with love. Rabbi Baruch builds on his earlier comments about the story of Jonah and its connection to Yom Kippur, saying, “HaShem is seeking people who are grieved over their sins, want to be forgiven, and then serve G-d according to His will for their lives.” Since fleeing God’s plan is actively choosing separation from Him, Yom Kippur is also a beautiful time to enter back into His presence.

In many ways, it seems like Jonah’s story could have ended after Chapter 3, when Jonah finally obeyed God and the city of Nineveh repented. The last chapter of the book of Jonah feels like an afterthought, an uncomfortable blot on the otherwise well-rounded plot. Yet, it is perhaps the most important chapter of all. It’s evident that while Jonah agrees to God’s plan after his traumatic experience in the belly of the great fish, he does so out of acknowledged responsibility and a sense of duty, still maintaining his base argument that the city of Nineveh does not deserve God’s forgiveness.

After Nineveh repents, he complains about the Lord’s lovingkindness, saying: “Ah, Lord, was not this what I said when I was still in my country? Therefore I fled previously to Tarshish; for I know that You are a gracious and merciful God, slow to anger and abundant in lovingkindness, One who relents from doing harm” (Jon. 4:2). Jonah has set out on several journeys at this point—Tarshish, Sheol, Nineveh—but this final chapter shows the most important journey yet––the journey into God’s heart. As Rebetzin Heller writes in her “Jonah and the Whale” article, “He was a prophet and awareness of God was not a novelty to him. But recognition of the depths of God’s mercy was.”

The Lord’s response to Jonah’s outburst is one question: “Is it right for you to be angry” (Jon. 4:4)? Jonah doesn’t respond. He sits outside the city and watches, hoping the Lord will decide to punish Nineveh after all. But it’s not the last time we’ll hear that question from the Lord. He causes a kikayon plant (vine) to grow up over Jonah as a shade, then the next day sends a worm to destroy it, at which point Jonah grows angry and wishes for death. Then comes God’s question again: “Is it right for you to be angry about the plant” (Jon. 4:9)? This time, Jonah responds with certainty.

The Lord’s response to Jonah is the final passage in the book of Jonah. We never hear Jonah’s answer. We don’t hear if he learns from the kikayon plant and the worm; we don’t hear if his heart softens, but we do hear God’s heart, which is more important. The Lord says: “You have had pity on a plant for which you have not labored, nor made it grow, which came up in a night and perished in a night. And should I not pity Nineveh, that great city, in which are more than one hundred and twenty thousand persons who cannot discern between their right hand and their left—and much livestock” (Jon. 4:10–11)?

Many scholars believe the reference to 120,000 people who don’t know their right hand from their left is actually a reference to children. That means there were hundreds of thousands more people the Lord was sparing in His act of mercy. He contrasts Jonah’s pity for a plant he didn’t labor for with God’s pity for Nineveh, implying the great city and all its people are something for which He, the God of land and sea, has labored as well. They are the works of His hands. Though they have fallen into wickedness, God’s heart is still for their restoration.

How vast and unimaginable is this kind of love. It’s the same love and patience that brought Jonah to a place of obedience, and the same love that leads us into repentance as well. The psalmist writes of this love in verses strangely linked to Jonah’s own journey:

“Your mercy, O Lord, is in the heavens;

Your faithfulness reaches to the clouds.

Your righteousness is like the great mountains;

Your judgments are a great deep;

O Lord, You preserve man and beast.

How precious is Your lovingkindness, O God!

Therefore the children of men put their trust under the shadow of Your wings” Psalm. 36:5–7

Today the book of Jonah cautions us regarding the futility of resisting God’s call on our lives. It’s a manual for the steps of proper repentance when we do wrong. But most of all, it’s a picture of His deep and patient mercy––the same mercy that pursued a fallen kingdom when its name was cursed among the nations and gently taught Jonah to look on all people with His compassion. That same mercy pursues and teaches us today.

Bull, Geoffrey T. The City and the Sign: An Interpretation of the Book of Jonah. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1970.

Scherman, Rabbi Nosson and Rabbi Meier Zlotowitz, eds. Trei Asar: The Twelve Prophets Vol. 1. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, Ltd., 1995.

http://www.aish.com/h/hh/yom-kippur/guide/48955321.html

http://www.torahclass.com/archived-articles/402-the-sign-of-jonah-by-rabbi-baruch

All logos and trademarks in this site are property of their respective owner. All other materials are property of Bridges for Peace. Copyright © 2025.

Website Site Design by J-Town Internet Services Ltd. - Based in Jerusalem and Serving the World.